There’s a channel on YouTube called The Proper People. It’s two guys who travel all over the United States (and in a few cases, elsewhere too) exploring abandoned buildings, and recording both the exteriors and interiors for posterity, since many of these buildings suffer from massive decay and are often slated for demolition. These buildings have histories and stories that otherwise would be lost to time.

They are incredibly respectful of the buildings they explore, and they will not break open locked doors or windows, and only traverse open and unlocked doors or openings borne out of natural decay. They never take anything from the sites they visit, and abhor what urban explorers call “staging”, where you move furniture and objects around to invoke or imply stories and things that aren’t there. Their videos are also very calm, muted, quiet, and only occasionally use atmospheric music for some of the more artistic shots. As a sidenote, they also happen to have the absolute best intro music of all time.

One of the things you quickly notice as you see these buildings, and explore their interiors, is just how solidly made and beautifully detailed they were. Whether they’re exploring an 19th century Kirkbride mental asylum, an early 19th century power plant, or a mid-20th century hospital – they all tend to be made not just to serve a function, but also to be beautiful and solid, both inside and out. Walls, ceilings, and doorways are beautifully detailed in masonry or woodwork, light fittings are solid and ornate, and even access corridors or storage basements have gorgeous vaulted ceilings, decorated walls, and ornate pillars.

The contrast to modern buildings couldn’t be starker. Buildings and workplaces of today are littered with drop ceilings, flimsy dividers, open plans, endless amounts of glass, all in styles so minimalist it just makes spaces feel cold, uninviting, and lacking in human scale. Modern buildings and interiors are temporary, ephemeral, built not for humans, but to a bottom line and some designer’s fancy – these old hospitals, factories, and even power plants are permanent, enduring, and made to human scale. They served as much as a status symbol for whatever ruthless capitalist owned the building as they did as a place for that same ruthless capitalist to extract wealth from mistreated workers.

This juxtaposition, of the minimalist, soulless, flimsy and cheap-looking exteriors and interiors of modern buildings on the one hand, and the beautifully detailed, skillfully crafted, and human-scale exteriors and interiors from these older buildings on the other, is something that kept creeping back into my mind during my use of the MNT Reform. This is a device built by people who deeply care, who are very opinionated, and know exactly what they want to make – very much the opposite of the cookie-cutter dime-a-dozen laptops that flood the market today.

MNT was so kind as to send me a Reform, at some risk to them because I am definitely not the kind of customer the Reform is typically aimed at. Yet, after a few months of use, I can confidently say this is one of the most unique devices I’ve ever used, and one that’s worth every cent. Let’s explore why.

Brutalist hardware

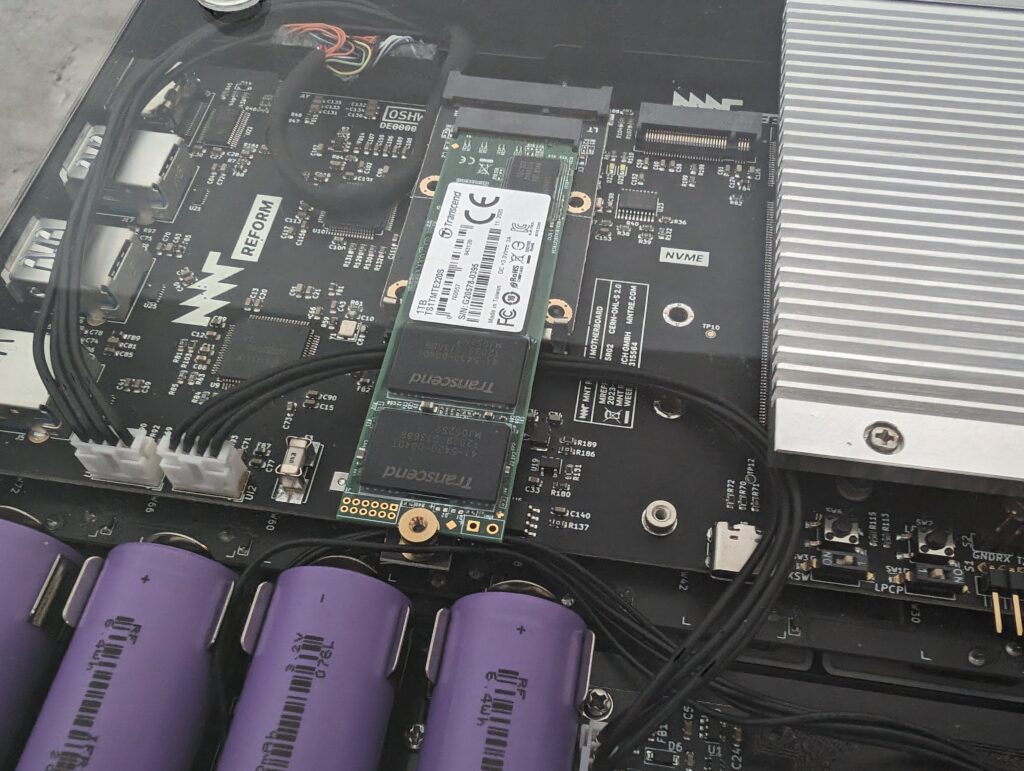

Let’s first dive into what, exactly, the Reform is. At its core, it’s an ARM-based laptop designed to run Linux, developed and built by a small team of people in Berlin. The Reform is unique in that it is designed to be open hardware, fully repairable and highly modular and upgradeable. It consists of a mainboard with an mPCIe slot, an M.2 slot for NVME SSDs, 16GB eMMC storage, and uniquely, a slot for a System-on-Chip module roughly the size of an SO-DIMM module that contains the processor and RAM. The keyboard and pointing device are internally connected through USB 2.0 and easily replaceable, too.

The Reform is defined as much by what it does not have as by what it does have. You won’t find any surveillance devices inside the Reform – no webcam, no microphones, nothing. There have been laptops with little privacy switches or sliding covers for the webcam, but I don’t think I’ve seen a modern laptop that eschews cameras and microphones since the late ’90s. It’s one of the many examples of the Reform’s opinionated design choices.

The configuration MNT sent me consists of the aforementioned mainboard, coupled with one of the processor modules they offer – in my case, the RCM4 A311D, which sports four 2.2GHz Cortex-A73 cores and two 1.8GHz Cortex-A53 cores, 4GB of LP-DDR4 RAM, and an ARM Mali G52 MP4 GPU that supports OpenGL/ES 3.1 through Panfrost. This module also supports Wi-Fi 5 and Bluetooth 5.0 through the integrated RTL8822CS.

The A311D is just one of many modules available for purchase for the Reform, and during the writing of this review, MNT also added a brand new SoC module to its lineup – the RK3588, the most powerful option available for the Reform. It packs 4 ARM Cortex-A76 cores (up to 2.4GHz) and 4 ARM Cortex-A55 cores (up to 2.2GHz), 16GB or 32GB of RAM, and 128GB or 256GB of eMMC storage. It also sports an ARM Mali-G610 MP4 4-core GPU.

Like with all other modules, the drivers for the A311D in my model are completely open source. When it comes to firmware, however, the A311D is not fully open source; there’s closed-source code in the Wi-Fi firmware and the boot/TF-A firmware. The other modules all also have various bits of closed firmware, except for the RKX7 module that uses a Kintex-7 FPGA and hence comes with a hefty price tag. Using the RKX7 module, you can have a fully open source laptop, from operating system down to the firmware, which is, as far as I can tell, unique.

However, the amount of closed firmware code for each of the other boards is relatively small, and in some cases – such as with the LS1028A – can be avoided, too. If you care about using as little closed-source code as possible on your computers, but you also want a capable, modern laptop, I’m honestly not entirely sure if there’s even any competition for the Reform. Considering how small the MNT team is, this is a remarkable achievement, and definitely something they can be proud of.

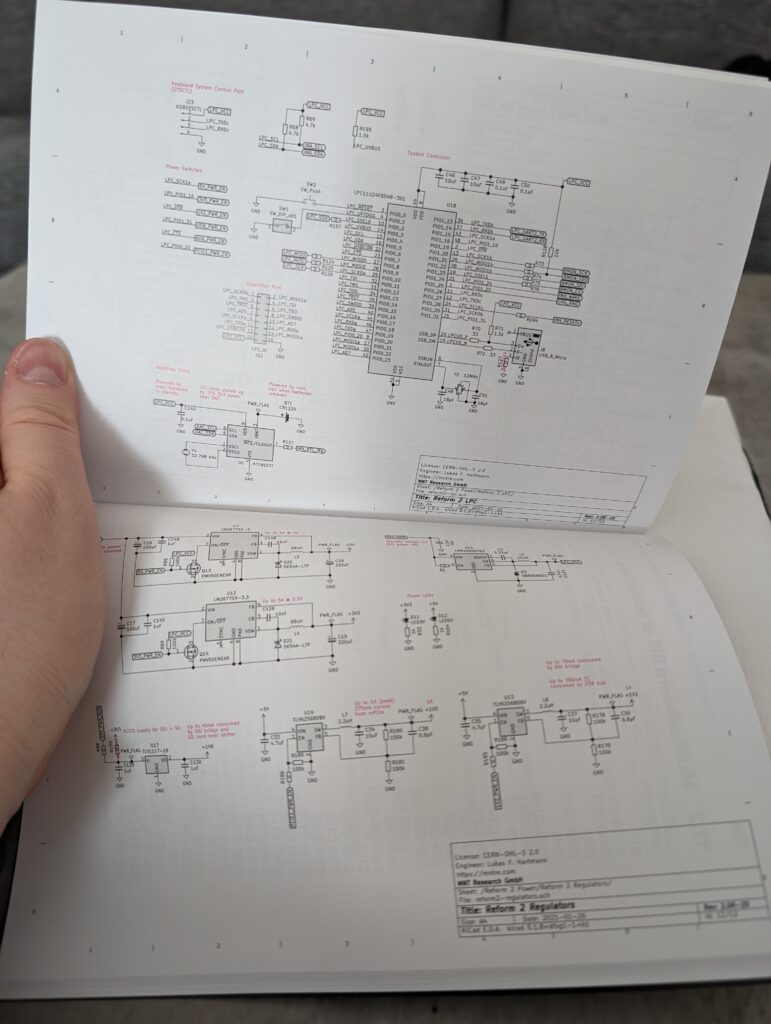

MNT takes it one step further, though, and goes out of its way to let you know which module makes its schematics and CAD sources available. It should come as no surprise, of course, that the schematics and CAD sources for everything else – casing, motherboard, custom parts, and so on – are all available from MNT, too. This focus on schematics sounds entirely alien to most people today, but it used to be the norm to get schematics with the computer you bought, allowing you to make modifications, repair damage, and generally gain understanding of how your computer worked.

Speaking of schematics, the unique experience the Reform offers starts with something I normally don’t really care about – unboxing. The Reform comes in a beautiful box, and is accompanied by a nice sleeve made of vegan leather, entirely custom for the Reform and handmade in Berlin. You also get something in the box that’s quite unique, something I only vaguely remember from my youth, an art form lost to the mists of time: a goddamn paper manual. It details all the various aspects of the machine, the software, and how to use it. And near the end of the manual?

Printed schematics.

In 2024, it’s pretty much unheard of for any laptop, smartphone, or tablet to come with an actual printed manual, especially not one as nice and in-depth like the Reform one. It contains usage instructions, detailed parts replacement instructions, the aformentioned detailed schematics, and even bills of materials for the various parts of the machine. In contrast, most other laptops will ship with a useless one-page quickstart guide, a few legally mandated warranty and safety leaflets, perhaps some stickers to proudly display your corporate loyalty, and if you’re lucky a QR code you have to blindly trust that may take you to a manual. Seeing a full, paper manual, like in the olden days, with so much information, is very refreshing and welcome.

Moving from the accessories to the actual laptop itself, and you’ll be in for an entirely different experience than from any other laptop. The first thing you notice when you pick it up is just how much of a chonker the Reform is. It clearly harkens back to the laptops of the early to mid ’90s, and comes in at a hefty 29 x 20.5 x 4 cm, and it weighs a solid 1.9 kg. Don’t let the ’90s styling fool you, though – unlike the ’90s fragile plastic that’s become the nemesis of retrocomputing enthusiasts the world over, the Reform is made almost entirely out of thick sheets of aluminium – save for the bottom, which we’ll get to later – with a solid internal structure, giving the whole laptop a level of solidity I simply didn’t expect. There’s no bending, flexing, or twisting any part or angle of this machine.

The Reform is angular and industrial, all the way around, again taking a page out of ’90s laptop design and construction. It’s unlike anything else on the market today.

Flipping the device over reveals the real star of the show: a thick sheet of transparent plastic, giving you a clear view of the gorgeous insides of the machine. MNT has clearly put a lot of effort into making the insides looks amazing, and they’ve certainly hit the mark – this is a work of art, and I can’t get enough of looking at it. The symmetrical individual battery cells, the black PCBs, the shining, silvery heat sink, the exposed cabling – it’s all very attractive.

It’s not just for looks, though, as there’s a lot of function in this form. The symmetrically laid-out battery cells are, of course, user-replaceable, and as such, this design makes them easily accessible. The ribbon cable connecting the input device to the mainboard is also easily accessible, which is useful since you can opt for either a trackball or a touchpad, and of course, you can change your mind later.

There’s also a lot of space in here for activities, as those with the right skills are encouraged to mod and expand the laptop to their heart’s desire. Going onto the MNT forums, you can find all kinds of mods and expansions, from people stuffing cellular modems and UART ports into their Reforms, to a mad lad who removed half of the battery cells to make space for an additional Ethernet port. On top of that, future SoC modules and heat sinks might require more internal space, so having room to spare aids in future-proofing.

Going around the laptop, there’s a ton of ports to play around with. On the left side, you’ve got the barrel power plug, an Ethernet port, an audio jack, and the SD card slot used too boot the system (depending on your setup). On the right side, there’s three USB-A ports and a full-size HDMI port. The three USB ports are USB 2.0 on the SoC module my machine shipped with, but USB 3.0 on all the other modules. The port selection is more than enough for a laptop of this size, but I would’ve preferred it to have USB-C charging instead of using a barrel jack, and having USB-C ports in general would’ve been nice for future-proofing.

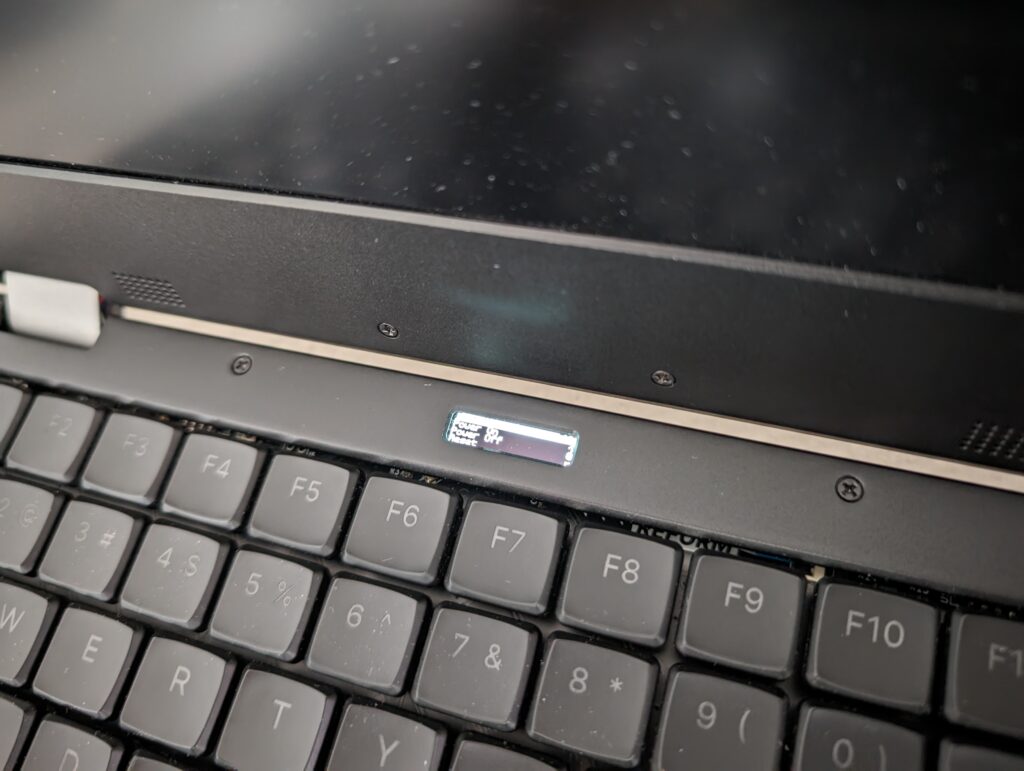

The MNT logo is stamped into the metal of the lid, and opening the lid up reveals a few more unique aspects of the laptop. First and foremost, instead of a trackpad, my model came with the optional trackball, surrounded by five clicky, mechanical buttons. The keyboard is fully mechanical, evenly backlit, and entirely custom-designed. At the top of the deck, between the display and the keyboard, sits a tiny black and white OLED, used to control several aspects of the device.

The trackball is great. It’s smooth, feels great to the touch, and the clicky, mechanical ‘mouse’ buttons are something I’ve never seen before. The bigger buttons on the side are the main left and right buttons, and while holding down either of the corner buttons, the trackball will scroll, and the middle button is, well, the middle mouse button. Of course, these buttons are all programmable, and on top of that, you’re free to replace the trackball with the trackpad yourself if you don’t like it. I do actually like the trackball, though, and got used to it very quickly.

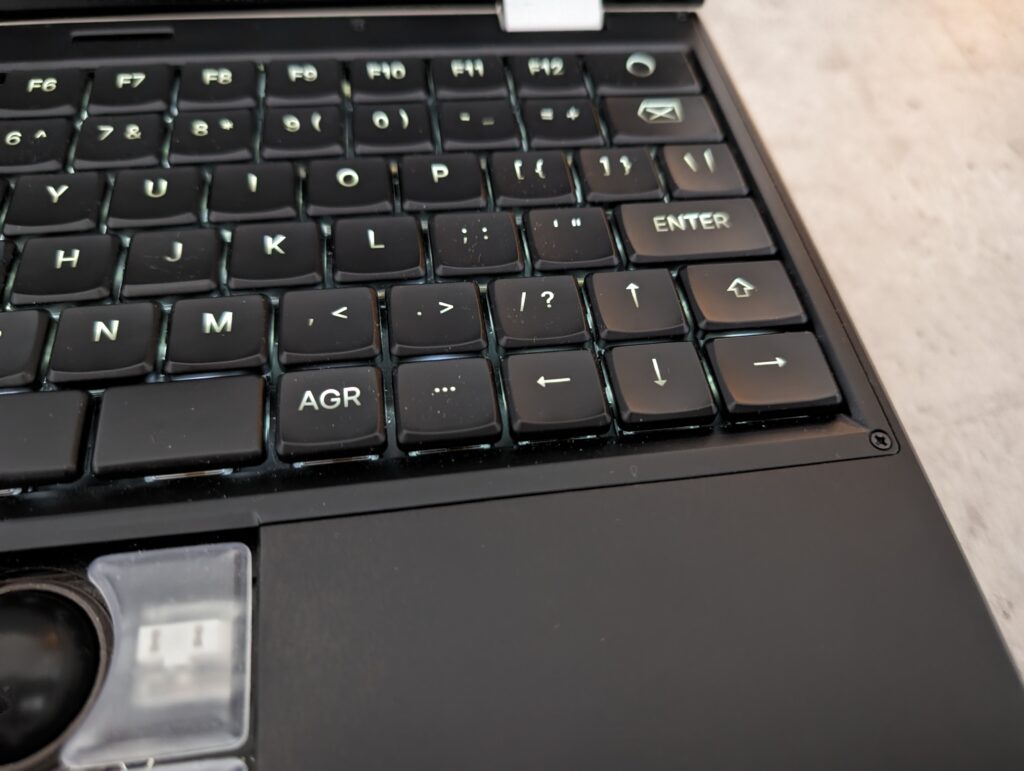

I’m a bit more torn on the keyboard, though. It feels and sounds absolutely amazing, without that high-pitched springy sound I tend to dislike. The keys have just enough travel to not become comical, as some mechanical keyboard tend to go for, and the keycaps are quite stable. It’s the layout, however, that doesn’t work as well for me. The default layout moves the left control key to where caps lock normally is, which I know quite a few people prefer, but I do not. There are a few other layout choices that are odd, but nothing too extreme, and you’re of course entirely free to reprogram the keyboard and move the keycaps around.

One choice, though, bothers me a lot: the right shift key sits to the right of the up arrow key, and because my hands are not very large, I have issues hitting it with my right pinky. I continuously end up hitting the up arrow key, which is infuriating during typing. I’m not entirely sure how I would address this myself, and for now, it makes typing on the keyboard a very conscious affair. It’s not a ‘get used to it’ issue; it’s a physical issue of my pinky simply not being long enough to comfortably hit that right shift key. That being said, keyboards are deeply personal, and your experience could easily be entirely different.

The little OLED display offers several options, like turning the device on and off, checking the battery status, turning up or down the keyboard backlight, and checking the system’s status. Of course, this, too, is entirely open and programmable, so you can do whatever you want with this display by hacking away at its firmware. For instance, the person who removed half of the battery cells edited the firmware to make sure it wouldn’t display “0%” for the missing cells.

The display is far better than it has any right to be, and at 1920×1080 at 12″, it’s razor sharp, plenty bright, and looks great. I had expected the display to be a possible pain point – good displays at reasonable prices are a lot harder to find than people think – but my worries were unfounded, and I simply have no complaints about the display whatsoever.

Two tiny speakers sit at the base of the display, and while they get the job done, they’re not particularly great. Spoken word sounds totally fine and acceptable, but things like music tends to sound tinny, a bit sharp, and gets unpleasant quick as you up the volume. For any possible future revision or follow-up model, I hope MNT considers making use of the ample space in the base to add some beefier, more high quality speakers. It’s not a dealbreaker or anything, but something of note if music playback is absolutely essential to you.

The word that comes to mind when handling this hardware is industrial. The aluminium panels seem thicker than on most other laptops, and aside from the trackball, you’re not going to find any curves or swoops here. It’s all angular, with exposed screws and an incredibly satisfying and assuring clunk when you close the lid, almost like a solid car door. The goal of this design clearly wasn’t to be elegant or graceful, but to be almost brutalist.

But that doesn’t mean this is a case of form over function – MNT clearly made tons of clear affordances for function here, like the tons of space for mods, the ease with which the internals can be changed and altered, and its upgradeability. It also happens to be entirely passively cooled, so there’s no fans and noise, which is also a testament to this design being very, very functional.

It’s a massive counter to modern laptop design, and I love it.

The price of the Reform is more reasonable than I initially expected. The current base model, with the A311D SoC module, without an NVMe or any of the accessories mine came with, costs €1200, which, considering how niche and unique this product is, I find a remarkably reasonable price for a laptop that, thanks to its upgradeability and repairability, can grow with you as new SoC modules become available.

My exact configuration, which adds a 1TB NVMe, the sleeve, and the printed manual, comes in at €1498. If you want the recently announced, faster RK3588 SoC module, add €200. Note that since MNT is based in Berlin, customers outside the EU might face additional import duties and fees.

Familiar software

The software experience of the MNT Reform is far less interesting or exciting than its hardware, and that’s a good thing. It runs plain Debian with some modifications by MNT, and much like when I reviewed Raptor’s POWER9 hardware, the beauty of Linux is that assuming the architecture is decently supported, there’s really not much difference between running Linux on, say, POWER9 or ARM on the one hand, and x86 on the other. All the same packages are (generally) available in both repositories, so all your favourite applications, tools, and other stuff are right there, just as if you were using an x86 machine.

To turn the machine on, you first have to connect the batteries internally – an easy process described in the manual – because they ship disconnected to prevent battery drain. Second, you need to put the supplied SD card in the SD card slot – in my case, it contained the bootloader – and then finally turn the machine’s System Controller on with the circle button in the top-right of the keyboard. The small OLED will come to life, and offer up several options in a menu, navigable through the keyboard. Select the option to boot the actual machine, and off you go.

There are several different setups you can use to boot the Reform, and it uses U-Boot to make them possible. Depending on your SoC module, you can boot from SD card, an NVMe drive, or eMMC storage, and I’m assuming things like USB or network booting are possible as well. The machine MNT sent me was set up with the operating system installed on the NVMe drive, but with the bootloader on the included SD card. While the Reform is clearly focused on supporting and running Linux, it should theoretically support any operating system that supports the SoC module you’re using, such as the various BSDs, and technically Windows on ARM, too, if you’re the kind of individual who loves watching the world burn?

Once the process is complete, you end up at the familiar Linux login prompt – this is a Linux system. I know this. Here you will find some of the modifications to Debian MNT has made. Most importantly, it lists some often-used commands you might want to use, how to start the two desktop environments that come preinstalled, and so on. This is a great addition to regular Debian, because it lists some of the things that MNT has prepared for its users that you otherwise would not be aware of unless you had read the manual.

You can either choose to keep using the system through the command line – not an uncommon occurrence for a lot of the kind of people interested in this device, I’m sure – or load up one of the two preinstalled desktop environments MNT has set up out of the box: a tiling setup using sway, and a more traditional windowing environment using wayfire. Both of them have been modified and adapted to integrate nicely with the hardware, with things like battery information, display brightness controls, and so on, as well as a few other niceties. Since I’m a KDE user, MNT also preinstalled KDE for me, something I would’ve done myself anyway, since I’m not a huge fan of the ‘assemble your own GUI’ types of environments things like sway and wayfire tend to be used for (but to each their own, of course!).

From here on out, I would guess most Reform owners go their own separate ways, building out their computing environment to their own exacting specifications. The preinstalled sway and wayfire environments offer good starting points; minimalist setups you can configure further as you may like. More complete environments, like the aforementioned KDE, but also GNOME, Xfce, or whatever else is available in the Debian repositories are of course a command away, as well. This is a Linux system. You know this.

My experience with using the Debian installation on the Reform has been rather uneventful, just as you’d expect. I’m not a performance benchmarker, so all I can do is relay my experiences using the machine for day-to-day work. KDE works and runs without any issues, and performance is fine – applications open fast, perform well, and I didn’t notice any unexpected stutters. Unsurprisingly, testing the sway and wayfire environments yielded the same results. I didn’t try any GTK environments like GNOME or Xfce, but I doubt the experience would be any different.

Before long, you’ll forget you’re using a laptop that isn’t x86. In that sense, the story here is identical to Raptor’s POWER9 workstations; as a Linux user, moving between different architectures like x86, ARM, and POWER is almost entirely transparent, and your favourite applications and tools are just right there, working as intended.

Mostly.

Of course, there are always things that are tied entirely to x86 and won’t be available, but in the case of the Reform, I don’t think any of them really matter. First and foremost, it comes as no surprise that gaming isn’t really a thing here, since Steam is not available on ARM Linux, and even if it were, virtually none of its games would be. You can use tools like box86 to run some x86 games on ARM, though, but it’s still relatively early in development, and it’ll need a lot more work and compatible games to become a viable option.

The second class of applications you won’t find on ARM Linux are things like Discord, Slack, and similarly coded applications. These are websites masquerading as applications using entire Chromium rendering engines, and their respective parent companies are generally not interested in supporting anything but x86. Luckily, though, these applications are almost always also available on the web, so you can just load them up in your browser and use them that way if you really must.

There is one piece of software I want to talk about in more detail, and that’s Firefox. I’m not exactly sure where the problem lies, but Firefox tends to eat up quite a bit of processor power, and more complex websites like the WordPress backend, YouTube, and the various online CAT tools I use for my job definitely have performance issues. Typing in the WordPress backend or my CAT tools often has delays and stutters, and things like going full screen on YouTube takes several seconds, and loading the various parts of the YouTube website is often quite slow. Video playback is not the issue here; YouTube’s website is. Regular websites load, render, and perform entirely normally and without any issues, so it seems to be restricted to complex web apps and unoptimised websites.

It’s really the only case where I noticed any substantial downside to using the Reform compared to my other, mainstream x86 devices, and while not a major, gamebreaking issue, it does bother me. I also tried Chromium, which seemed to perform just a little better and more consistently. I’m not sure where the problem lies, but my uneducated guess would be that Firefox is simply less optimised for Linux on ARM than Chromium. I’m hoping subsequent releases of Firefox will address these problems, because there’s no chance in hell I’m using anything based on Google’s Chromium. I’ll gladly take some minor lag or stutters if it means not having to contribute to Chrome’s staggering monopoly.

Battery life has been only so-so, perhaps 3-4 hours per charge, depending on what I was doing. It’s definitely not class-leading or anything, so if you spend a lot of time unplugged from the wall you might want to ensure you’re bringing the charger with you, but as always with battery life, your experience may be entirely different. On top of that, this is a 1.9 kg laptop, so it’s not the most portable device to begin with.

Approachable community

There’s one more thing I’d like to mention, and that’s the sense of community and just how approachable MNT is. When you read about some of the modding projects people have done, you’ll often see references to MNT helping the modders out, and the MNT forum and various Mastodon accounts underline this. If you have a Reform and wish to perform a hardware or software mod, MNT most likely would love to help you with tips, advice, suggestions, and answers to any questions you might have.

Such direct lines of communication with the very people building the hardware you’re trying to use and alter to your liking is rare.

Entirely unique

The MNT Reform is entirely unique.

There is nothing else like it on the market. I am not aware of any other laptop designed entirely by and for open source, open hardware, and Linux enthusiasts that does its utmost best – within reason – to be entirely open, from hardware down to firmware. A laptop that encompasses the ideals of user ownership, repairability, and upgradeability, ideals that once used to be the norm in the world of computing. You’d expect a strong focus on such ideals would compromise the user experience, but nothing could be further from the truth.

I’ve done all my usual laptop tasks with the Reform, from browsing the web, to watching video, to my job as a translator involving complex CAT tools in the form of complex web apps, and more. Aside from the aforementioned small issues with Firefox and the larger issue of the right shift key, using the Reform and Debian on ARM has been a great experience. I could easily use this as my only laptop, and I would barely have to change anything about my usage patterns.

MNT proves that the ideals of open hardware need not to be an impediment to usability. You could give the Reform to any normal user not particularly interested in technology, and after some remarks about the chunky design, I doubt they’d have any trouble using it for their day-to-day tasks. Even stripped from all of its additional, idealistic benefits, the Reform is just a great laptop running a popular Linux distribution, and that in and of itself makes it a worthwhile purchase to consider if you’re looking for a new Linux laptop.

Add to this the reasonable price, the repairability and upgradeability to increase the device’s longevity, and the Reform is a steal. If you also happen to be a tinkerer and programmer, capable of and interested in creating hardware and software modifications to truly make the Reform uniquely yours, then there’s really no other laptop that even comes close.

Hmm no real risc-v option yet. I assume it would be possible to make a module for that though.

Very nice review. This hardware definetely deserves all the love it can take, there is (as you expressed) nothing that compares.

I am waiting for a MNT Pocket Reform (which is probably getting shipped soon).

MNT Reform cheks many things that no other commercial (buy and get a ready to use product) do. In my situation this goes to use a industry standard/generic user replaceable battery, fanless, unmatched motherboard upgradeable (right now you can choose between 6 different system on chip board), special attention to details like programmable/mechanic keyboard and pointer devices (those are incredible in itself), repairability, a fancy OLED secondary progammable little status display and of course the ethics and mindset behind it all. Not only you won’t easily find products with all these features combined, but you will hardly find any with a combination of some of them. Of course these are the things I really value, but there are other features that other will value than I’m not talking about.

While it is more expensive than other platforms, the world moves where the money is put, and this company well deserves being there.

First of all I commend MNT for creating the product, it seems really nice and well thought out and fairly future proof. There is one concern I have, that is probably going to be a deal breaker for me. Uboot/Device tree. I’ve had too many Uboot devices that only work with custom kernels, preventing the upgradability and life time of the device. Its not using stock releases from Ubuntu/Debian/Fedora. but modified Debian. The whole allure of Linux for me, is the ability to easily swap distros. If one misbehaves, oh well the other will work fine. Now if I want to use a new feature even one in Debian’s new release, I probably have to wait for MNT to update their sources before I can upgrade. For the price of a Raspberry pi or most single board computers, I can forgive this, but not at full laptop prices.

Bill Shooter of Bul,

I can’t speak to MNT Reform since I have no experience with it. It seems nicer than the laptops I own.

About your point though, you are spot on! Having separate sources for software is invaluable as a customer! Almost all of the hardware I own with software that is proprietary and/or only supported exclusively by the hardware vendor has lost software support long before the hardware itself fails. The result…”I’ve have to throw out yet another piece of working hardware over a damn software support issue”, which is so messed up. The x86 architecture is more or less grandfathered into different norms from long ago where installing a new OS from outside sources is common and expected. Other architectures have great technical merit and usually run more efficient, but the risk of being tethered to a single entity that drops the ball on EOL support is nearly 100%. This is so aggravating and bad for the planet. I try to vote with my feet, but unfortunately the majority of the time, if it ain’t x86, software support will fail before the hardware does.

I’m just noticing just how much I sound like a cheerleader for intel there, haha.

I’ve been seeking x86 alternatives including ARM for multiple decades, but the vendor locking keeps creating so many problems. I am so disappointed they don’t have ubiquitous open standards that work everywhere to give us a strait forward means of decoupling commodity hardware and software. Unfortunately many manufacturers want customers to remain tethered to them and they want to control the levers of planned obsolescence. These business incentives conflict with open platforms, which is likely why there’s so little progress.

At least x86 computers matured decades ago before these changes. if x86 were invented today it would likely suffer from all the same tight coupling and non-viable software alternatives.

Same. I keep posting about the arm initiative to accomplish this. it exists, but no one uses it. outside of a few hobbyist boards. I have no idea why it didn’t take over.

https://www.arm.com/architecture/system-architectures/systemready-certification-program

Hi Tom,

thanks for testing this machine ! What can you tell about its performance ? any chance you can run some benchmarks on it ? at the very least the good old unixbench (which can be run from the phoronix test suite I think https://github.com/phoronix-test-suite/phoronix-test-suite/

once installed: it’s run like this :

phoronix-test-suite benchmark byte.

There are several modules for the Reform. One user posted his experiences here https://community.mnt.re/t/ls1082a-questions/1863. Also in some months an RK3588 is about to be available which will be the fastest module available.

Just from memory, there are SOCs with ARM A53, A55, A72, A73, A75 and A76 cores to choose from.

The Mali g52 whilst fully compatible with the open source Lima and Panfrost drivers is not a fast circut. It is only 36% faster tan the by now very old Adreno 508 budget GPU found in budget Xperia mobile devices from 2017 like the Xa2 (discovery).

Optimistically 163.2Gigaflops, or 27.2Gigaflops in its weakest configuration… since it is the MP4 that means its somewhere between 108.8-163.2 depending on how each EU is configured.

So yeah… amazingly weak for even a mobile GPU these days. By comparison my Legion Go handheld does 8.6Teraflops… like I can lock it to 30FPS and low-medium settings and it still look better than PS4 Pro graphics.

Would have been nice to have USB type C, including for power (instead of the barrel connector).

With pretty much all phones now being USBC, and laptops also often using USBC for power it’s just more convenient. I have a 300W 4x C adapter on my desk, and they are becoming more and more common everywhere.

Now if i forget my power adapter i can almost always borrow one, or buy one easily in any local store. Not so with barrel connectors where you need to find the correct size, correct polarity and correct voltage out of a large number of possibilities.