In my lifetime, there’s been one ecosystem I deeply regret having missed out on: the Sun Microsystems ecosystem of the late 2000s. At that time, the company offered a variety of products that, when used together, formed a comprehensive ecosystem that was a fascinating, albeit expensive alternative to Microsoft and Apple. While not really intended for home use, I’ve always believed that Sun’s approach to computing would’ve made for an excellent computing environment in the home.

Since I was but a wee university student in the late 2000s living in a small apartment, I did not have the financial means nor the space to really test this hypothesis. Now, though, Sun’s products from that era are decidedly retro, and a lot more approachable – especially if you have incredibly generous readers. So sit down and buckle up, because we’ve got a long one today.

If you wish to support OSNews and longform content like this, consider becoming a Patreon or donating to our Ko-Fi. Note that absolutely zero generative “AI” was used in the writing of this article. No “AI” writing aids, no “AI” summaries, no ChatGPT, no Gemini search nonsense, nothing. I take pride in doing research and writing properly, without the “aid” of digital parrots with brain damage, and if there’s any errors, they’re mine and mine alone. Take pride in your work and reject “AI”.

The Ultra 45: the central hub

In the early 2000s, it had already become obvious that the future of workstations lied not with custom architectures, bespoke processors, and commercial UNIX variants, but with standard x86, off-the-shelf Intel and AMD processors, and Windows and Linux. The writing was on the wall, everyone knew it, and the ensuing consolidation on x86 turned into a veritable bloodbath. In the ’80s and ’90s, many of these ISAs were touted as vastly superior x86 killers, but fast-forward a decade or two, and x86 had bested them all in both price and performance, leaving behind a trail of dead ISAs.

Never bet against x86.

Virtually none of the commercial UNIX variants survived the one-two punch of losing the ISA they were married to and the rising popularity of Linux in the workstation space. HP-UX was tied to HP’s PA-RISC, and both died. SGI’s IRIX was tied to MIPS, and both died. Tru64 was tied to Alpha, and both died. The two exceptions are IBM’s AIX and Sun’s Solaris. AIX workstations were phased out, but AIX is still nominally in development for POWER servers, but wholly inaccessible to anyone who doesn’t wear a suit and has a massive corporate spending budget. Solaris, meanwhile, which had long been available on x86, saw its “own” ISA SPARC live on in the server space until roughly 2017 or so, and was even briefly available as open source until Oracle did its thing. As a result, Solaris and its derivative Illumos are still nominally in active development, but in the grand scheme of things they’re barely even a blip on the radar in 2025.

Never bet against Linux.

During these tumultuous times, the various commercial UNIX vendors all pushed out systems that would become the final hurrahs of their respective UNIX workstation lines. DEC, then owned by HP, released its AlphaStation ES47 in 2003, marking the end of the road for Alpha and Tru64 UNIX. HP’s own PA-RISC architecture and HP-UX met their end with the HP c8000 (which I own), an all-out PA-RISC monster with two dual-core processors running at 1.1GHz. SGI gave its MIPS line of machines running IRIX a massive send-off with the enigmatic and rare Tezro in 2003. In 2005, IBM tried one last time with the IntelliStation POWER 285, followed a few months later by the heavily cut-down 185, the final AIX workstation.

And Sun unveiled the Ultra 45, its final SPARC workstation, in 2006. Sun was already in the middle of its transition to x86 with machines like the Sun Java Desktop System and its successors, the Ultra 20 and 40, and then surprised everyone by reviving their UltraSPARC workstation line with the Ultra 25 and 45, which shared most – all? – of their enclosures with their x86 brethren. They were beautiful, all-aluminium machines with gorgeous interior layouts, and a striking full-grill front, somewhat inspired by the PowerMac G5 of that era.

And ever since the Ultra 45 was rumoured in late 2005 and then became available in early 2006, I’ve been utterly obsessed with it. It’s taken almost two decades, but thanks to an unfathomably generous donation from KDE e.V. board member and FreeBSD contributor Adriaan de Groot, a very unique and storied Sun Ultra 45 and a whole slew of accessories showed up at my doorstep only a few weeks ago. Let’s look back upon this piece of history that is but a footnote to most, but a whole book to me – and experience Sun’s ecosystem from around 2006, today.

First and foremost, I want to express my deep gratitude to Adriaan de Groot. Without him, none of this would have been possible, and I can’t put into words how grateful I am. He donated this Ultra 45 to me at no cost – not even the cost of shipping – and he also shipped another box to me containing a few Sun Ray thin clients, completing the late 2000s Sun ecosystem I now own. Since the Ultra 45 was technically owned by KDE e.V. – more on that below – I’d also like to thank the KDE e.V. Board for giving Adriaan permission for the donation. I’d also like to thank Volker A. Brandt, who sent me a Sun Ray 3, a few Ultra 45 hard drive brackets, and some other Sun goodies.

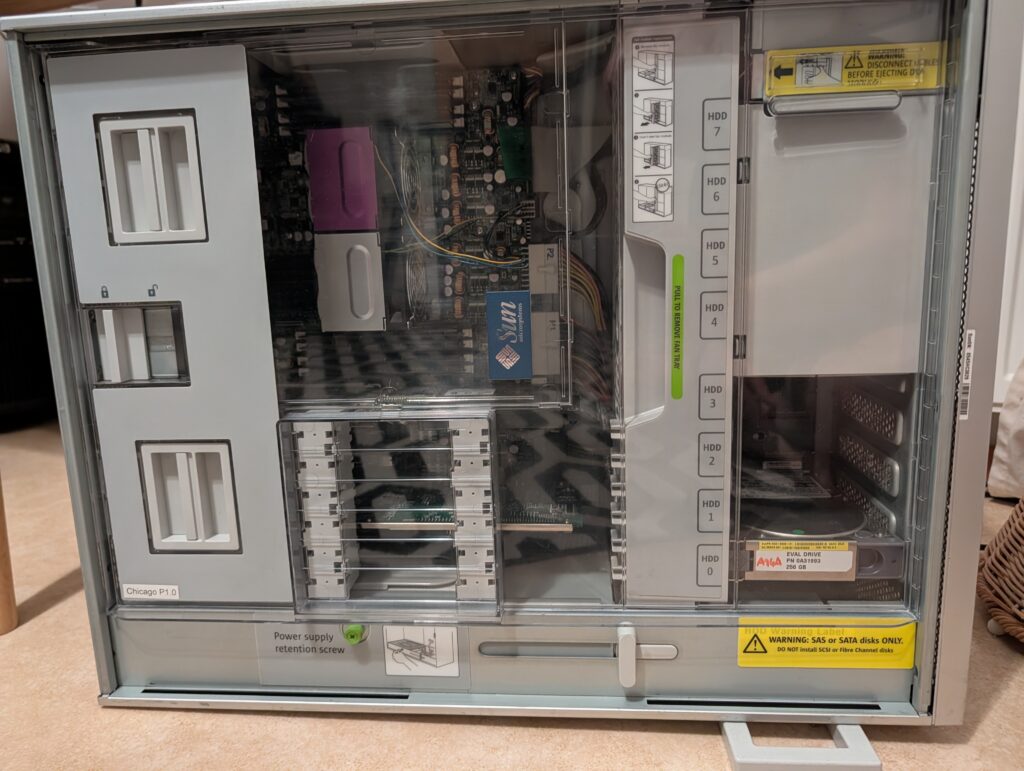

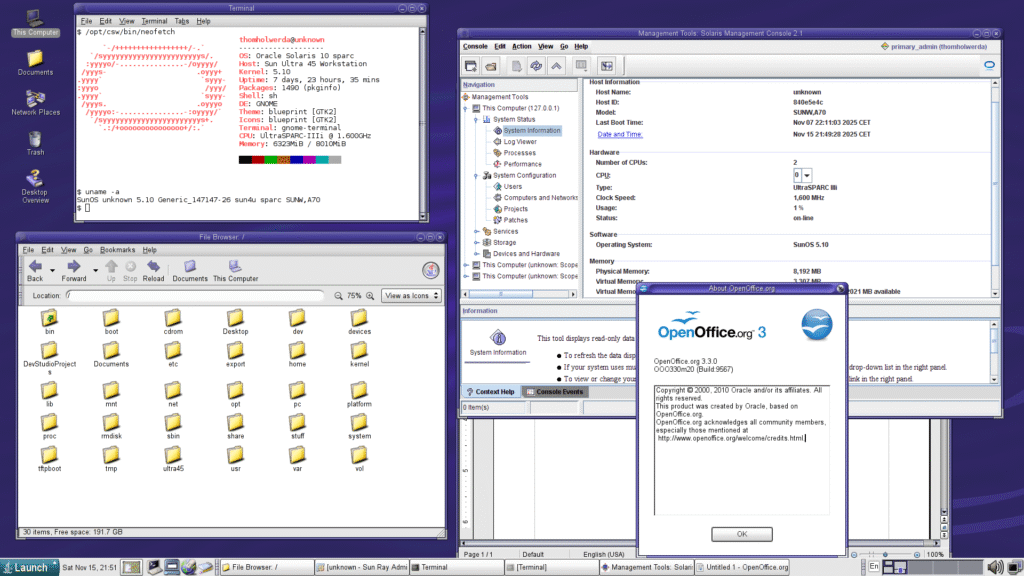

The Sun Ultra 45 De Groot sent me was a base model with an upgraded GPU. It had a single UltraSPARC IIIi 1.6Ghz processor, 1GB of RAM, and the most powerful GPU Sun ever released for its SPARC workstation line, the Sun XVR-2500, a rebadged 3Dlabs Wildcat Realizm with 256MB of GDDR3 memory. Everything else you might need – sound, networking, and so on – are integrated into the motherboard. It also comes with a slot-loading, slimline DVD drive, a 250GB 7200 RPM SATA hard drive, and its massive 1000W power supply.

First order of business was upgrading the machine to match the specifications I wanted, with the most important upgrade being doubling the processor count. Finding a second 1.6Ghz UltraSPARC IIIi processor was easy, as they’re all over eBay and won’t cost you more than a few dozen euro excl. any shipping; they were also used in various Sun SPARC servers and are thus readily available. The bigger issue is finding a second CPU cooler, as they are entirely custom for Sun hardware and quite difficult to find. I found a seller on eBay who had them in stock, but be prepared to pay out the nose – I paid about €40 for the CPU, but around €160 for the cooler, both excl. shipping.

Installing the second CPU and cooler was a breeze, as it’s no different than installing a CPU or cooler on any other, regular PC. The processor was detected properly by the machine, and the cooler whirred to life without any issues, but of course, if you’re buying used you may always run into issues with parts. If you want to save some money, there is a way to use a specific cooler from a Dell workstation instead (and possibly others?), but I wanted the real deal and was willing to pay for it.

The second upgrade was the RAM. A mere 1GB wasn’t going to cut it for me, so alongside the processor and cooler I also ordered a set of four 1GB RAM sticks, the exact right kind, and ECC registered, too, as the machine demands it. This turned out to be a major issue, as I discovered the machine simply would not boot in any way, shape, or form with this new RAM installed. It didn’t even throw up any error message over serial, and as such, it took me a while to pinpoint the issue. Thankfully, I remembered I had a broken, non-repairable Sun server from the same era as the Ultra 45 lying around, and it just so happened to have 8✕1GB Sun-branded RAM sticks in it. I pilfered the sticks out of the server, stuck them in the Ultra 45, and the machine booted up without any problems.

I later learned from people on Fedi who used to work with Sun gear from this era that RAM compatibility was always a major headache. It seems the wisest thing to do is to just buy Sun-branded memory kits, because there’s very little guarantee any generic RAM will work, even if it is entirely identical to whatever sticks Sun slapped its brand stickers on. For now, 8GB is enough for me, but in a future moment of weakness, I may order 8✕2GB Sun-branded memory to max the Ultra 45 out. The main reason you may want to invest in a decent amount of RAM is to make ZFS on Solaris 10 happy, so take that into account.

Aside from these upgrades to the base system itself, I also planned two specialty upgrades in the form of two unique expansion cards. First, a Sun Flash Accelerator card to speed up ZFS’s operations on the spinning hard drive, and second, a SunPCi IIIpro, which is an entire traditional x86 PC on a PCI-X card, the final iteration of a series of cards designed specifically for allowing Solaris SPARC users to run Windows inside their workstation. I’ll detail these two expansion in more detail later in the article.

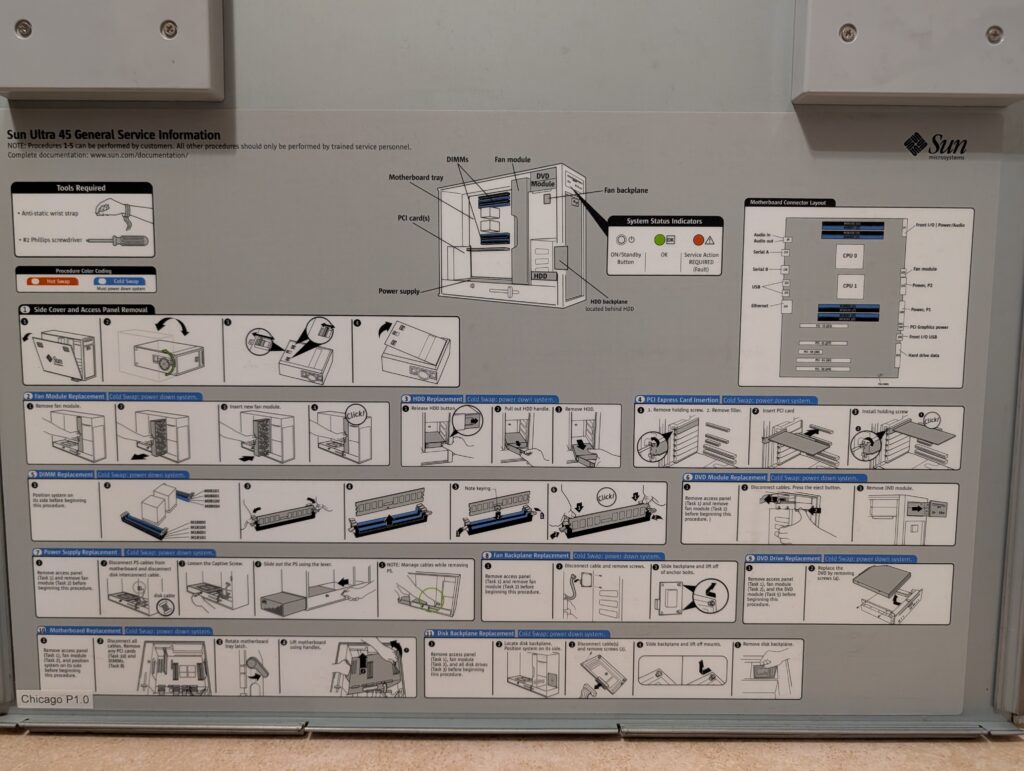

What’s in an Ultra 45?

The Sun Ultra 45 was launched as one of four brand new Sun workstations, with an entirely new design shared between all four of them. Two were successors to Sun’s first (okay, technically second) foray into x86 workstations, the Java Workstation: the Ultra 20 (single-socket Opteron) and Ultra 40 (dual-socket Opteron). These were mirrored by the Ultra 25 (single-socket UltraSPARC IIIi) and Ultra 45 (dual-socket UltraSPARC IIIi). However, where the Ultra 20/40 were genuine improvements over their Java Workstation predecessors, the story gets a bit more muddled when it comes their SPARC brethren.

Let’s take a look at the most powerful direct predecessor of the Ultra 45, the Sun Blade 2500 Silver. The table below lists the core specifications of the Blade 2500 Silver compared to the Ultra 45. Notice anything?

| 2500 Silver (2005) | Ultra 45 (2006) | |

| CPU | 2×UltraSPARC IIIi 1.6Ghz | 2×UltraSPARC IIIi 1.6Ghz |

| CPU cache | 64KB data 32KB instruction 1MB L2 cache | 64KB data 32KB instruction 1MB L2 cache |

| RAM | DDR SDRAM (PC2100) 8 slots 16GB max. ECC registered | DDR SDRAM (PC2100) 8 slots 16GB max. ECC registered |

| GPUs | XVR-100 XVR-600 XVR-1200 | XVR-100 XVR-300 XVR-2500 |

| PCI | 6 PCI slots 64bit 3×33/66MHz 3×33MHz | 2×PCIe size ×16/lanes ×8 1×PCIe size ×8/lanes ×4 2×PCI-X 100MHz/64bit |

| Storage interface | 1×Ultra160 SCSI | SAS/SATA controller 4 disks |

As you can see, the Ultra 45 was only a very modest upgrade to the Blade 2500 Silver. While the upgrades the Ultra 45 brings over its predecessor are very welcome, it’s not like upgraded expansion slots and the move to SAS/SATA would make Blade 2500 owners rush out to upgrade in droves. For heavy graphics users, the new XVR-2500 graphics card may have been tempting as it is inherently incompatible with the Blade 2500 (it uses PCIe), but I have a feeling many customers at the time would’ve probably just opted to move to x86 instead. For all intents and purposes, the Ultra 45 was a slim upgrade to its predecessor.

The story gets even more problematic for the SPARC side of Sun’s workstation business when you consider the age of the 2500 line. While the 2500 Silver was released in early 2005, its only upgrade compared to the 2500 Red was a clock speed bump (from 1280Mhz to 1600MHz), and the 2500 Red was released in 2003. This means that the Ultra 45 is effectively a computer from 2003 with improved expansion slots and a fancy new case. As a final knock on the Ultra 45, its processor had already been supplanted by Sun’s first multicore SPARC processors, the UltraSPARC IV in 2004 and the UltraSPARC IV+ in 2005, and Sun’s first multicore, multithreaded processor, the UltraSPARC T1, in 2005. These chips would never make it to any workstations, being used in servers exclusively.

Sun clearly knew further investments in SPARC workstations were simply not worth it at the time, and thus opted to squeeze as much as it could out of a 2000-2003ish platform, instead of investing in the development of a brand new workstation platform built around the UltraSPARC IV/IV+/T1. In other words, while the Ultra 45 is the last and most powerful SPARC workstation Sun ever made, it wasn’t really the balls-to-the-wall SPARC workstation sendoff it could’ve been, and that’s a shame.

But this one is mine

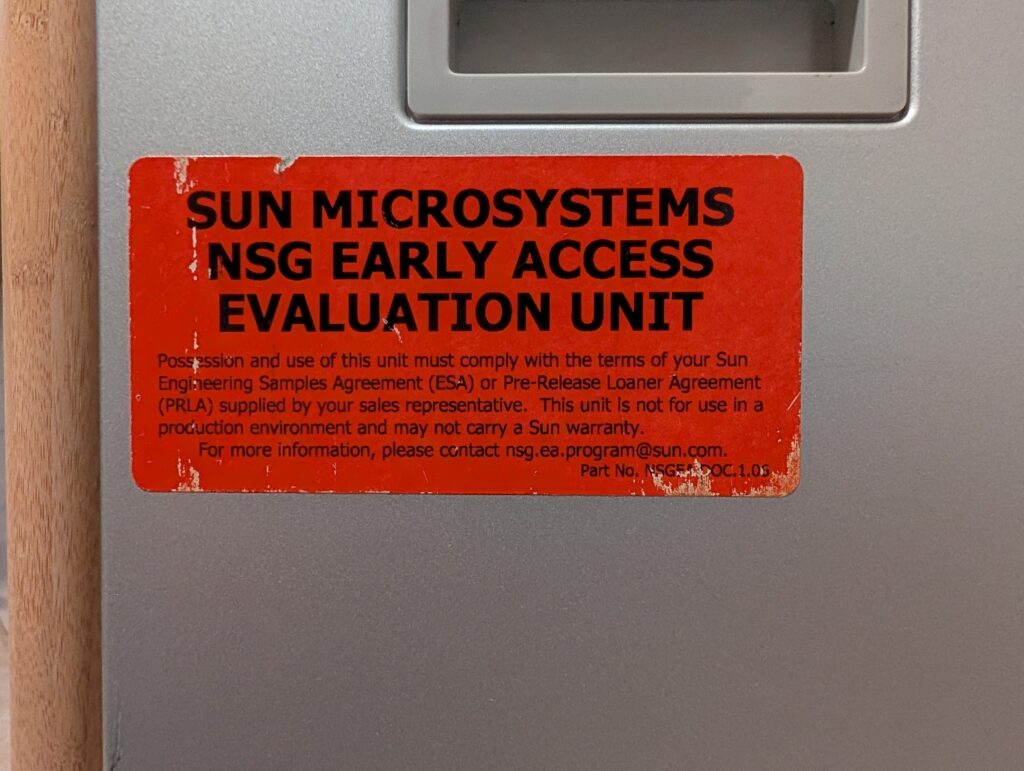

Now that we have a good idea of where the Ultra 45 stood in the market, let’s take a closer look at my specific machine. My Ultra 45 is not just any machine, but actually a pre-production model, or, in Sun parlance, an “NSG EARLY ACCESS EVALUATION UNIT”. The bright orange sticker on the side and the big yellow sticker at the top make it very clear this isn’t your ordinary Ultra 45.

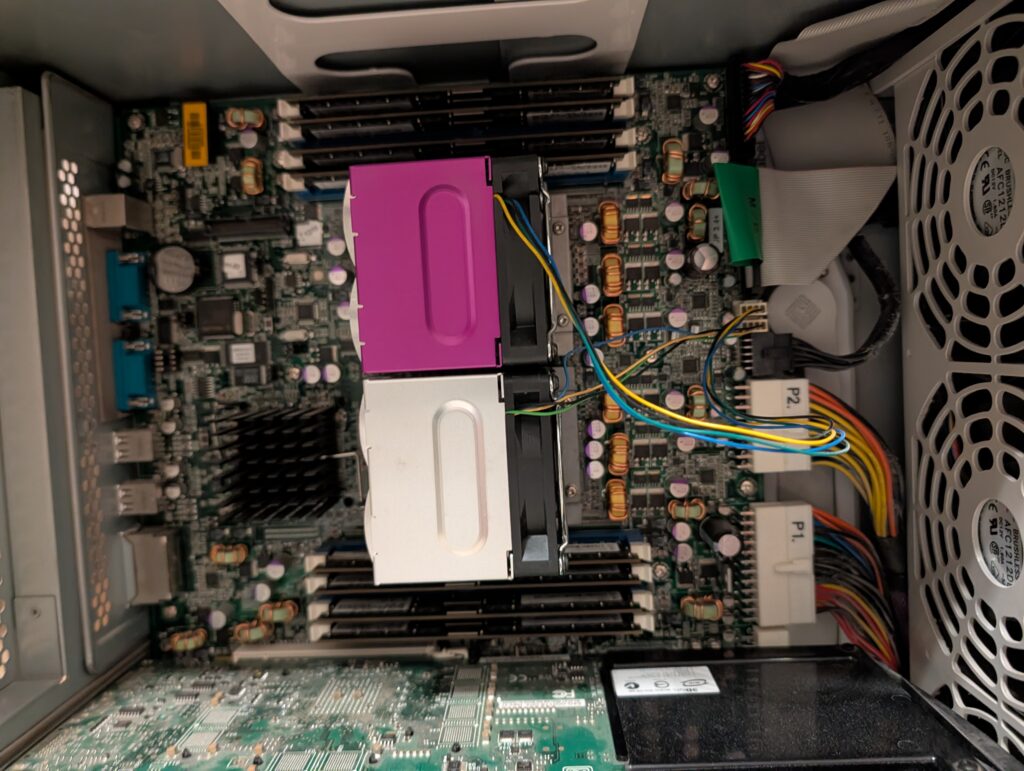

I’ve removed and cleaned some other sticker residue, but these will remain exactly where they are, as I consider them crucial parts of its unique history. The fact it’s a pre-production unit means there are some very small differences between this particular machine and the final version sold to consumers. The biggest difference is found on the inside, where my model misses the two RAM air ducts found on the final version; my wild guess is that during late-stage testing they discovered the RAM could use some extra fresh air, and added the ducts.

Another difference inside is that the original CPU cooler, which came with the machine, is purple, while the second CPU cooler I bought off eBay is silver. As far as I can tell based on checking countless photos online, all CPU coolers on final models were silver, making my single purple cooler an oddity. I’d love to know the story behind the purple cooler – Sun used purple a lot in its branding and hardware design at this point, and it could be that this is a cooler from one of their many server models. Other than the colour, it’s entirely identical to its silver counterpart.

On the outside, the only sign this is a pre-production model – other than the stickers – is the fact that the ports and LEDs on the front of the device are unlabeled, while the final models had nice and clear labels. My machine also lacked the “Ultra 45” badge at the bottom of the front panel, so I did a silly and spent around €50 (incl. shipping and EU import duties) on a genuine replacement. It clicks into place in a dedicated hole in the metal meshwork.

It’s the little details that matter.

On the front of my Ultra 45, there’s a strong hint as to it history: a yellow label maker sticker that says “KDE project”. Sun’s branch in Amersfoort, The Netherlands, donated (or loaned out?) this particular Ultra 45 to KDE e.V. back in 2008 or 2009, so that the KDE project could work on KDE for Solaris and SPARC. You can even find blog posts by Adriaan de Groot about this very machine from that time period. It served that function for a few years, I would guess up until around 2010, when Oracle acquired Sun and subsequently took Solaris closed-source again.

Since then, it’s mostly been sitting unused in Adriaan’s office, until he offered to send it to me (after confirming with KDE e.V. it could be donated to me). Considering KDE is an important part of the machine’s history, I’m leaving the little KDE label right where it is. Perhaps Sun sent out its preproduction machines to people and projects that could make use of it, which was a nice – and a little self-serving, of course – gesture. Now it’s getting yet another lease on life as by far my favourite (retro)computer in my collection, which is pretty neat.

The operating system

Once I had the machine set up and booting into the OpenBoot prompt, it was time to settle on the software I’d be running on it. Since I tend to prefer setting up machines like this as historically accurate as is reasonable, Solaris 10 was the obvious choice. Luckily, Oracle still makes the SPARC version of Solaris 10 available in the form of Solaris 10 1/13 as a free download. This article won’t go too deep into operating system installation and configuration – it’s straightforward and well-documented – but I do have a few notes I’d like to share.

First and foremost, if you intend to use ZFS as your file system – and you should – make sure you have enough RAM, as mentioned earlier, but also to start the installer in text mode. You can’t install on ZFS when using the graphical installer, in which you’ll be restricted to UFS. Both variants of the installer are easy to use, straightforward, and a breeze to get through for anyone reading OSNews (or anyone crazy enough to buy SPARC hardware in 2025). If you’ve never worked with SPARC hardware and Sun’s OpenBoot before, have a list of ok> prompt commands at hand to boot the correct devices and change any low-level hardware settings.

The 1/13 in Solaris 10 1/13 means the DVD ISO is up-to-date as of January 2013, and sadly, Oracle hides post-1/13 patchsets behind support contract paywalls, so you won’t be getting them from any official sources. There’s a few 2018 and 2020 patchsets floating around, as well as collections of individual patch files, but I’ve some issues with those. One of the major issues I ran into with a more recent patchset is that it broke the Solaris Management Console, a Java-based graphical tool to manage some settings. There is a fix, but it’s hidden behind Oracle’s dreaded support contract paywalls, so I couldn’t do anything about it.

I’m sure a later version of the Solaris 10 patchset – they’re still being made twice a year, it seems – addressed this issue, but none of those patchsets ‘leaked’ online. I did try to install the individual patches in the massive patchset one-by-one to avoid potentially problematic ones identified by their description, but it was a hell of a lot of work that felt never-ending, since you also have the dependency graph to work through and track. After a few hours of this nonsense, I gave up. I would love for Oracle to stop being needlessly protective over a bunch of patchsets for a dead operating system running on a dead architecture, but I don’t own a massive Hawaiian island so I guess I’m the idiot.

One of the things you’ll definitely want to do after installing Solaris 10 is set up OpenCSW. OpenCSW is a package manager and associated repository of Solaris 10-native SVR4 packages for a whole bunch of popular and useful open source programs and tools, with dependency tracking, update support, and so on. It’s incredibly easy to set up, just as easy to use, and installs its packages in /opt/csw by default, for neat separation. As useful as OpenCSW is, though, it’s important to note that most packages have not been updated in years, so it’s not exactly a production-ready environment. Still, it contains a ton of tools that make using Solaris 10 on SPARC in 2025 a hell of a lot easier, all installable and manageable through a few simple commands.

I have a few other random notes about using Solaris 10 on a workstation like this. First, and this one is obvious, be sure to create a user for your day-to-day use so you don’t have be logged in as the root user all the time. If you intend to use the Solaris Management Console, which offers a graphical way to manage certain aspects of your machine, you’ll want to create the Primary Administrator role and assign it to your user account. This way, you can use the SMC even through your regular user account since it’ll ask you to log into the primary administrator role.

Second, assuming you want to do some basic browsing and emailing, you’ll also want to install the latest possible versions of Firefox and Thunderbird, namely version 52.0 of both. You can either opt for basic tarball installation, or use the SVR4 packages available from UNIX Packages to make installation a little bit easier. Version 52.0 of Firefox is severely outdated, of course, so be advised; tons of websites won’t work properly or at all, and security is obviously out the window. A newer version will most likely not be released since that would require an up-to-date Rust port and toolchain for Solaris 10/SPARC as well, which isn’t going to happen.

In addition, if you’ve set up OpenCSW, you should consider adding /opt/csw/bin to your PATH, so that anything installed through OpenCSW is more easily accessible. Furthermore, Solaris 10 installs both CDE and the Java Desktop System – GNOME 2.6 with a fancy Sun theme – and I highly suggest using the JDS since it was properly maintained at the time, while CDE had already stagnated for years at that point. It’ll give you niceties like automatic mounting of USB sticks and DVDs/CDs, and make it much easier to access any possible network locations. Speaking of which – you’ll want to set up a SAMBA or NFS share so you can easily download files on a more modern machine, and subsequently make them accessible on your Solaris 10 machine. Both of these protocols are installed by default.

As a final note, there are three sources I use to find ancient software for these older UNIX systems (I use both Solaris 10 and HP-UX): fsck.technology, whatever this is, and the Internet Archive. You can find an absolutely massive pile of programs, software, operating system patches, and everything else in these three sources, including various ways to circumvent any copy protection schemes. I don’t care about the legality, and neither should you.

If you want to go for something more modern than Solaris 10, SPARC is still supported by a variety of operating systems, like NetBSD, OpenBSD, and a number of Linux distributions. Your best bet is to buy one of the lower-end GPUs, like the XVR-300 or XVR-600, as the XVR-2500 is not supported by the BSDs, but may work on Linux. I haven’t tried any of them yet – this article is long enough as it is – but I will definitely try them out in the future.

The future island owners among you may also be wondering about Illumos and its various derivatives and distributions, like OpenIndiana and personal OSNews darling Tribblix. While they all do support SPARC, it’s spotty at best, especially on workstations like the Ultra 45. SPARC servers have a better success rate, but the Ultra 45 specifically is unsupported at this point due to bugs preventing Illumos and friends from even booting. The good news, though, is that the people working on the SPARC variants have access to Ultra 45 machines, and work is being done to fix these issues.

Now, let’s move on to the two specialty upgrades I bought for this machine.

Accelerating ZFS

The transition from spinning hard disk drives to solid-state drives was an awkward time. Early on, SSDs were still prohibitively expensive, even at small sizes, but the performance benefits were obviously significant, and everyone knew which way the wind was blowing. During this awkward time, though, people had to choose between a mix of solid state and spinning drives, leading to products like hybrids drives, which combined a small SSDs with a large hard drive to get the best of both worlds. As prices kept coming down, people could opt for a small SSD for their operating system and most-used applications, storing everything else on spinning drives.

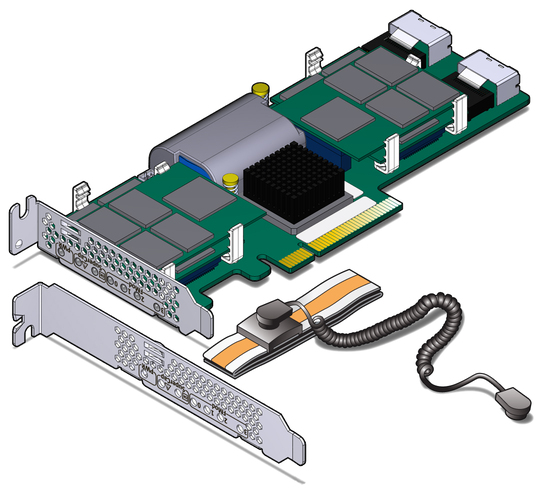

A hybrid drive doesn’t necessarily have to exist as a single, integrated product, though; depending on factors like operating system, controller, and file system, you could also assign SSDs as dedicated accelerators. This is where Oracle’s line of Flash Accelerator cards – the F20, F40, and F80 – come into play. These were released starting in roughly 2010, and consisted of several replaceable flash memory modules on a PCIe card. They were rebranded LSI Nytro Warpdrives with some custom firmware, which can actually be flashed back to their generic LSI firmware to turn them into their white label LSI counterparts.

Oracle’s Flash Accelerator cards are remarkably flexible, because their firmware presents the individual flash modules as individual block devices to the Solaris 10 operating system. This way, you can assign each individual module to perform specific tasks, which, combined with the power of Solaris 10’s ZFS, gives people who know what they are doing quite a few options to speed up specific workloads. In addition – and this is pretty cool – these accelerator cards can also serve as a boot device, meaning you can install and run Solaris 10 straight from the accelerator card itself.

These cards come in a variety of sizes, and they’re incredibly cheap these days. They’re not particularly useful or economical for modern applications, but they’re still fun relics from an older time. And because they’re so cheap and plentiful on the used market, they’re a great addition to a retro project like my Ultra 45 – even if they’re technically intended for server use. I ordered a Flash Accelerator F20 on eBay for like €20 including shipping, giving me 96GB, spread out over four 24GB flash modules, to play with.

The card has two stacks of two flash modules, which can be removed and replaced in case of failure, as well as a replaceable battery. Sadly, the one I ordered didn’t come with the full-height PCI bracket, but even without any bracket, the card sits incredibly firmly in its slot. The card also functions as a host bus adapter, giving you two additional SAS HBA ports for further storage expansion. Do note that you’ll need to perform a reconfiguration boot of your SPARC system after installing the card, which is done by first dropping to the ok> prompt, and then executing boot -r. Once rebooted, the format command should display the four flash modules.

# format

Searching for disks…done

AVAILABLE DISK SELECTIONS:

0. c1t0d0 <ATA-HITACHIHDS7225S-A94A cyl 65533 alt 2 hd 16 sec 465>

/pci@1e,600000/pci@0/pci@9/pci@0/scsi@1/sd@0,0

1. c3t0d0 <ATA-MARVELLSD88SA02-D21Y cyl 23435 alt 2 hd 16 sec 128>

/pci@1e,600000/pci@0/pci@8/LSILogic,sas@0/sd@0,0

2. c3t1d0 <ATA-MARVELLSD88SA02-D21Y cyl 23435 alt 2 hd 16 sec 128>

/pci@1e,600000/pci@0/pci@8/LSILogic,sas@0/sd@1,0

3. c3t2d0 <ATA-MARVELLSD88SA02-D21Y cyl 23435 alt 2 hd 16 sec 128>

/pci@1e,600000/pci@0/pci@8/LSILogic,sas@0/sd@2,0

4. c3t3d0 <ATA-MARVELLSD88SA02-D21Y cyl 23435 alt 2 hd 16 sec 128>

/pci@1e,600000/pci@0/pci@8/LSILogic,sas@0/sd@3,0

Specify disk (enter its number):Now it’s time to decide what you want to use them for. I’m not a system administrator and I have very little experience with ZFS, so I went for the crudest of options: I assigned each module as a ZFS cache device for the ZFS pool I have Solaris 10 installed onto, which is stupidly simple (the exact disk names can be identified using format):

# zpool add -f <pool name> cache <disk1> <disk2> <disk3> <disk4>

To check the status of your pool and make sure the modules are now acting as cache devices:

# zpool status

pool: ultra45

state: ONLINE

scan: none requested

config:

NAME STATE READ WRITE CKSUM

ultra45 ONLINE 0 0 0

c1t0d0s0 ONLINE 0 0 0

cache

c3t0d0s0 ONLINE 0 0 0

c3t1d0s0 ONLINE 0 0 0

c3t2d0s0 ONLINE 0 0 0

c3t3d0s0 ONLINE 0 0 0

errors: No known data errorsThe theory here is that this should give the 7200 RPM SAS drive the ZFS pool in question is running on a nice performance boost. Now, this is mostly theory in my particular case, since I’m not using this machine for any heavy workloads in 2025, but perhaps if you were doing some heavy lifting back in 2010 on your Solaris 10 workstation, you might’ve actually seen some benefit.

Of course, this is anything but an optimal setup to get the most out of this hardware, but I already had a fully configured Solaris 10 install on the spinning hard drive and didn’t feel like starting over. Like I said, I’m no system administrator or ZFS specialist, but even I can imagine several better setups than this. For instance, you could install Solaris 10 in a ZFS pool spanning two of the flash modules, while assigning the remaining two flash modules as log and cache devices for the spinning hard drives you keep your data files on. In fact, Oracle still has a ton of documentation online about creating exactly such setups, and it’s not particularly hard to do so.

This F20 card wasn’t part of my original planning, and the only reason I bought it is because it was so cheap. It’s a fun toy you could buy and use on a whole variety of older systems, as long as they have PCIe slots and compatibility with PCIe storage. The entire card is just a glorified HBA, after all, and many operating systems from the past 20 years or so can handle such cards and its flash storage just fine.

Let’s move on to something more interesting – something I’ve been dying to use ever since I learned of their existence decades ago.

I put a computer in your computer so you can computer with other computers

Even in the ’90s, much of the computing world – especially when it came to generic office and home use – had already moved firmly to x86 and Windows. Sun knew full well that in order to entice more customers to even consider using SPARC-based workstations, they needed to be interoperable with the x86 Windows world, since those were the kinds of machines their SPARC workstations would have to interoperate with. So, from quite early on in the 1990s, they were working on solutions to this very problem.

Sun’s first solution was Wabi, a reimplementation of the Win16 API to allow a specific set of popular Win16 applications to run on non-x86 UNIX workstations. This product was licensed by other companies as well, with IBM, HP, and SCO all releasing their own versions, and eventually it was even ported to Linux by Caldera in 1996. Another solution Sun offered at the same time as Wabi was SunPC, a PC emulator based on technology used in SoftPC. SunPC was limited to at most 286 software, however, so if you wanted to emulate software that required a 386 or 486 – like, say Windows 3.x or 95 – you needed something more.

And it just so happens Sun offered something more: the SunPC Accelerator Card. This line of accelerator cards, for SBus-based SPARC workstations, contained a 486 processor (and one later model an AMD 5×86 processor) on an expansion card that the SunPC emulator could use to run x86 software that required a 386 or 486. With this card installed, SPARC users could run full Windows 3.x or Windows 95 on their workstations, albeit with a performance penalty as the SunPC Accelerator Card did not contain any memory; SunPC had to emulate the RAM.

With Sun’s SPARC workstations moving to more standard PCI-based expansion busses in the second half of the 1990s, Sun would evolve their SunPC line into the SunPCi (clever), and that’s when this product line really hit its stride. Instead of containing just an x86 processor, SunPCi cards also contained memory, a graphics chip, sound chip, networking, VGA ports, serial ports, parallel ports, and later USB and FireWire as well. A SunPCi card is genuinely an entire x86 PC on a PCI expansion card, and the operating system running on that x86 PC can be used either in a window inside Solaris, or by connecting a dedicated monitor, keyboard, mouse, speakers, and so on. Or both at the same time!

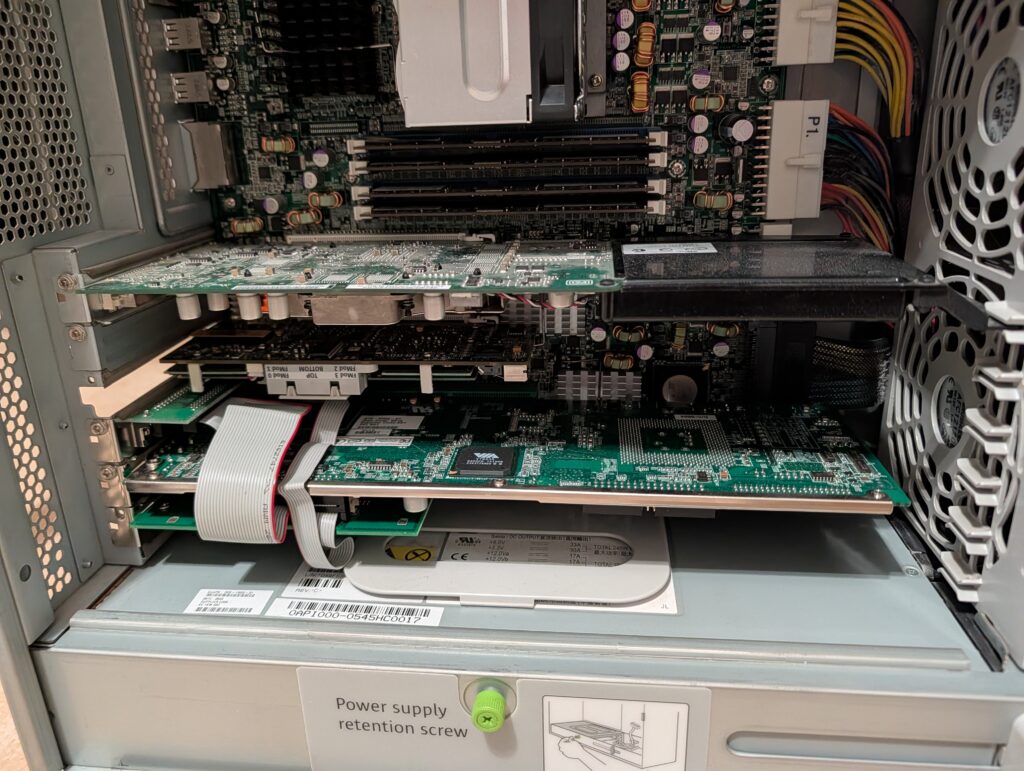

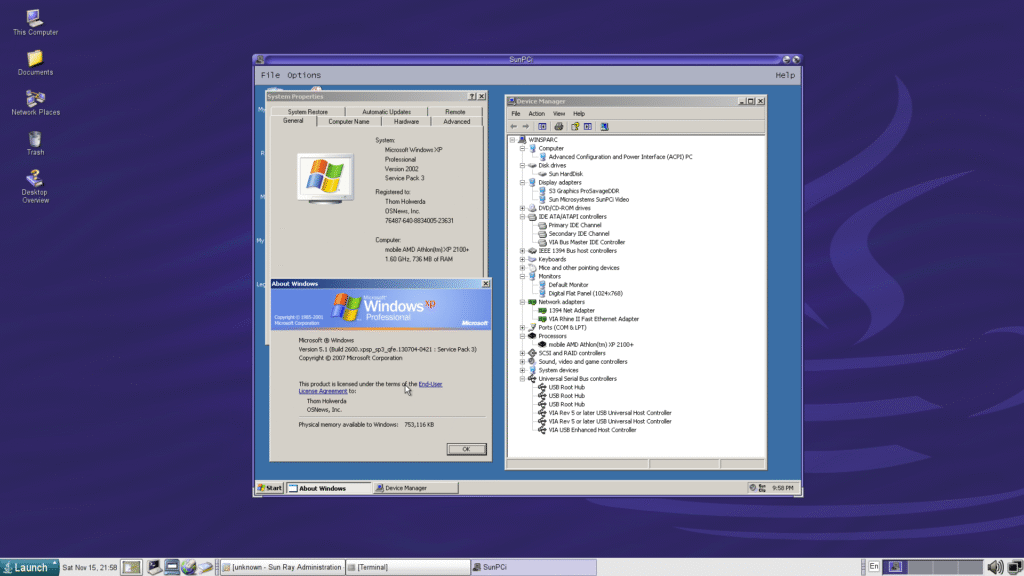

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Sun would release a succession of ever faster models of SunPCi cards, culminating in the last and most powerful variant: the SunPCi IIIpro, released in 2005. This very card is one of the reasons I was so excited to get my hands on a machine that could do it justice, so I splurged on a new-in-box model offered on eBay. This absolute behemoth of a PCI-X card contains the following PC hardware:

- Mobile AMD Athlon XP 2100+ at 1.60Ghz

- Two DDR SODIMM slots for a maximum of 1GB of RAM

- S3 Graphics ProSavage DDR

- A sound chip of indeterminate origin

- VIA Rhine II Fast Ethernet Adapter

The base card contains a VGA port, a USB port, Ethernet port, and audio in and out. The number of ports can be expanded with two optional daughter cards, one of which adds two more USB ports as well as a FireWire port, while the other one adds a serial and parallel port. These two daughter boards each require an additional PCI slot, but only the USB/FireWire one actually makes use of a PCI-X connector. In other words, if you install the main card and its two daughter boards, you’ll be using up three PCI slots, which is kind of insane.

By default, the card only comes with a single 256MB DDR SODIMM, which is a bit anemic for many of the operating systems it supports – as such, I added an additional 512MB DDR SODIMM for a total of 768MB of RAM. Unlike the Ultra 45 itself, it seems the SunPCi IIIPro is not particularly picky about RAM, so you can most likely dig something up from your parts pile and have it work properly. The card has a few other expansion options too, like an IDE header so you can use a real hard disk instead of an emulated one, but that would require some hacking inside the Ultra 45 due to a lack of power options for IDE hard drives.

Once you have installed the card – a fiddly process with the two daughterboards attached – it’s time to boot the host machine back up and install the accompanying SunPCi software. The last version Sun shipped is SunPCi Software 3.2.2 in 2004, and in order to make it work on my Ultra 45 I had to perform some workarounds. Searching the web seems to indicate the problems I experienced are common, so I figured I’d collect the problems and workarounds here for posterity, so I can spare others the trouble.

What you’ll need is the SunPCi Software 3.2.2, the latest version; you can find this in a variety of locations around the web, including in the software repositories I mentioned earlier in the article. The installation is fairly straightforward, but the post-install script might throw up an error about being unable to find a driver called sunpcidrv.2100. The fix is simple, but the odds of finding this out on your own are slim. Once the installation is completed, run the following commands as root to symlink to the correct drivers:

cd /opt/SUNWspci3/drivers/solaris/

ln -s sunpcidrv.280 sunpcidrv.2100

ln -s sunpcidrv.280.64 sunpcidrv.2100.64The second problem you’ll most likely run into is absolutely hilarious. If you try and start the SunPCi software with /opt/SUNWspci3/bin/sunpci, you’ll be treated to this gem:

Your System Time appears to be set in the future

I can't believe it's really Tue Nov 11 18:01:23 2025

Please set the system time correctlyThis error message comes from a bug in the 3.2.2 release that was fixed in patch 118591-04, so you’ll have to download that patch (118591-04.zip) from any of the countless repositories that hold it (here, here, here, etc.) and install it according to the instructions to remove this time bomb. I’m glad people have been willing to share this patch in a variety of places, because if this one remained locked behind donations to the Larry Ellison Needs More Island Fund I’d be pretty upset.

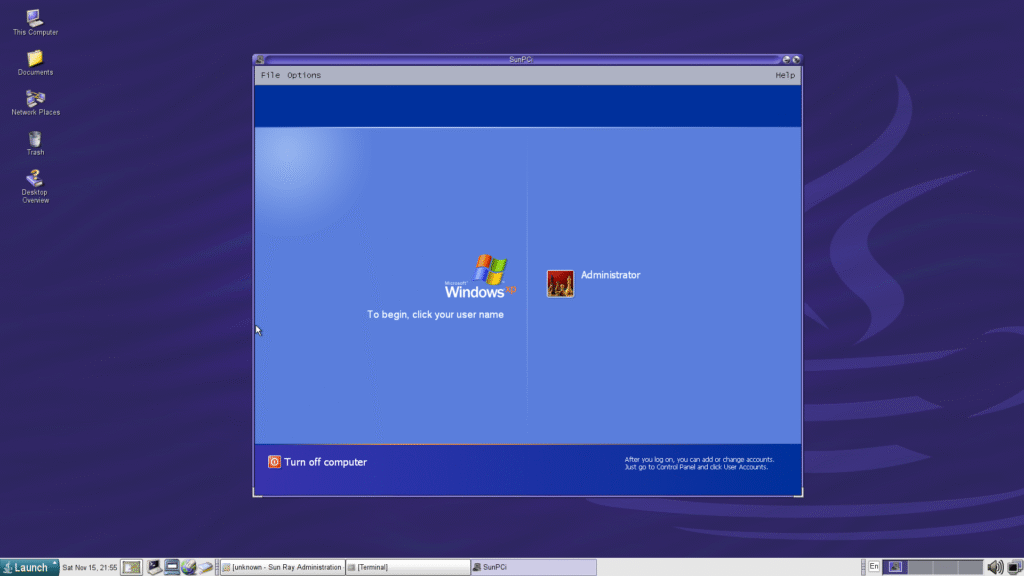

Once installed, the SunPCi software should start just fine, greeting you with a dialog where you can configure your emulated hard drive and select the operating system you wish to install. Provided you have the correct operating system installation disc, the operating system you select will automatically be installed onto the emulated hard drive. You’ll also see proof that yes, this card is really just a regular, run-of-the-mill PC: it boots up like one, it has a BIOS like any other PC, you can enter this BIOS, and you can mess around with it. It’s really just a PC.

Sun put a lot of effort into making the operating system installation process as seamless and straightforward as possible; in the case of Windows XP, for instance, the SunPCi software will copy the contents of your Windows XP disc to a temporary location, and slipstream all the necessary drivers and some other software (specifically Java Web Start, of course) into the Windows XP installation process. In other words, once the installation is completed and you end up at the Windows XP desktop, all proper device drivers have been installed and you’re ready to start using it.

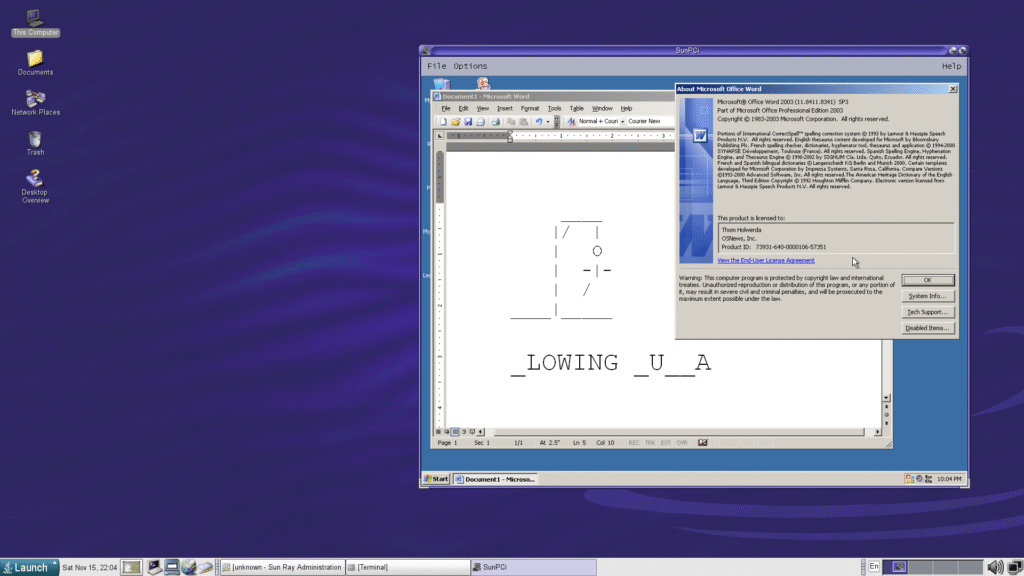

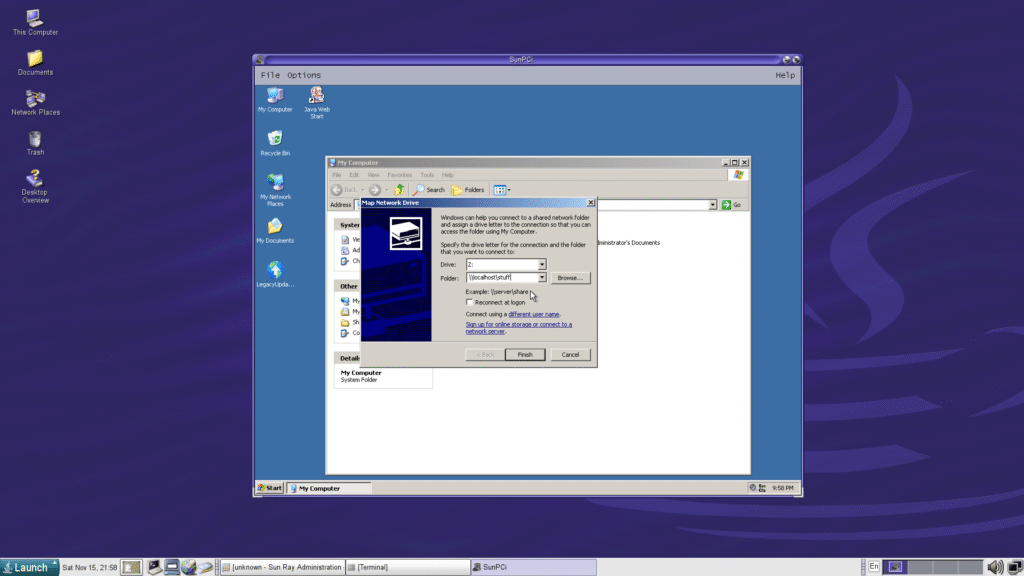

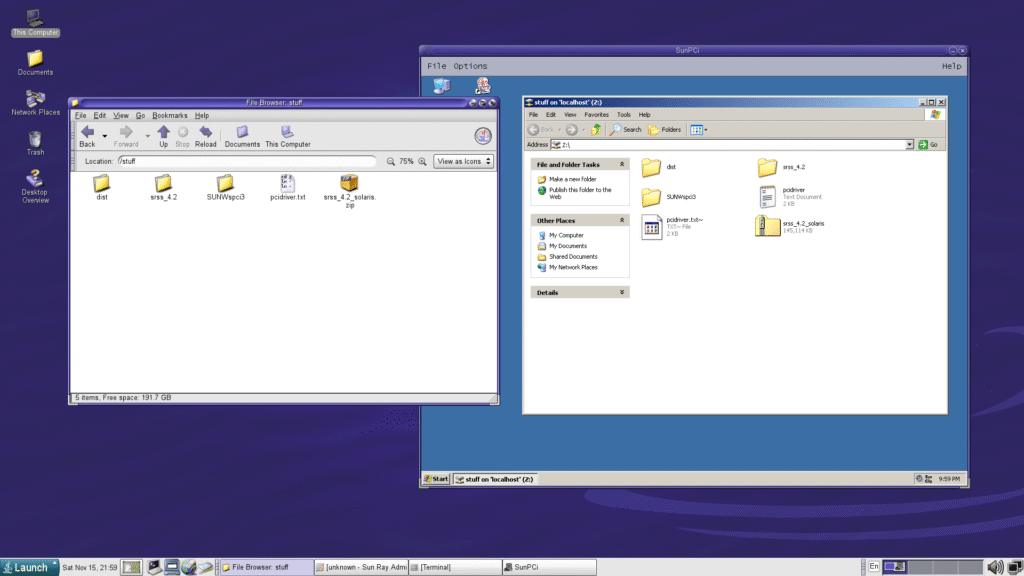

The amount of effort and thought Sun put into this product shines through in other really nice touches as well. For instance, inserting a CD or DVD into the Ultra 45’s drive will not only automatically mount it in Solaris, but also inside Windows XP – autorun and all. Making folders on the host’s file system available inside Windows XP is also an absolute breeze, as you can mount any folder on the host system inside Windows XP using Explorer’s Map Network Drive feature: \\localhost\home\thomholwerda, for instance, will make /home/thomholwerda available in Windows. You can also copy and paste text between host and client, and SunPCi offers the option to grow the virtual hard drive you’re using in case you need more space.

The installation procedure installs two different video drivers in Windows XP: one for the S3 Graphics ProSavageDDR, and one for the SunPCi Video. The former drives any external display connected to the SunPCi card, while the latter outputs to a window inside Solaris. If you need to do any graphics or video-related work, Sun strongly suggests you use the S3 chip by using an external display, and it’s obvious why. The performance of the SunPCi Video is so-so, and definitely feels like it’s rendering in software (which it is), so you can expect some UI stutters here and there. A nice touch is that there’s no need for the SunPCi window to “capture” the mouse pointer manually, as you can freely move your Solaris cursor in and out of the SunPCi window.

As for the performance of Windows XP – it will align more or less with what you can expect from a mobile Athlon from 2002, so don’t expect miracles. It’s entirely usable for office and related tasks, but you won’t be doing any hardcore gaming or complex, demanding professional work. The goal of this card is not to replace a dedicated x86 workstation, but to give Solaris/SPARC users access to the various office-related applications most organisations were using at the time, like Microsoft Office, IBM’s Domino, and so on, and it achieves that goal admirably.

There’s a ton of other things you can do with this card that I simply haven’t had the time yet to dive into (this article is already way too long), but that I’d like to come back to in the future. For instance, the list of officially supported operating systems includes not just Windows XP, but also Windows 2000, Server 2003, and a variety of versions of Red Hat (Enterprise) Linux (think Linux version ~2.4.20). The SunPCi software also contains an entire copy of DR-DOS 7.01, which is neat, I guess. Lastly, the user manual for the SunPCi software lists a whole lot of advanced features and tweaks you can play with, too.

I would also be remiss to note that you can actually use multiple SunPCi cards in a single machine, as that’s a fully supported configuration. You can totally get a big SPARC server, put multiple SunPCi cards in it, and let users log in remotely to use them, perhaps using Sun’s true thin client offering, Sun Rays. This is foreshadowing.

As for other operating systems – I’ve seen rumblings online that versions of NetBSD and Debian from the early 2000s were made to work on the SunPCi II (the previous model to what I have), but I can’t find any information on anything else that might work. The issue is that any operating system running on the card needs drivers for the emulated hard disk, which are obviously not available as those were made by Sun. Since the SunPCi IIIpro has an actual IDE connector, though, I’ve been wondering if it would at least be possible to boot and run an “unsupported” operating system using the external method (dedicated display, mouse, keyboard, etc.). If there’s interest, I can dive into this in the future and report back.

All in all, though, the SunPCi IIIPro is a much more thoughtful and pleasant product to use than I originally anticipated. Sun clearly put a lot of thought into making this card and its features as easy to use as possible, and I can totally see how it would make it palatable to use a SPARC workstation in an otherwise Windows-based corporate environment. Just load up Outlook or whatever Windows-based groupware thing your company used using the SunPCi software, and use it like any other application in your Solaris 10 SPARC environment. Since you can set the SunPCi software to load at boot, you’d probably mostly forget it was running on a dedicated PC on an expansion card, and your colleagues would be none the wiser.

To round out the Sun Microsystems ecosystem of the late 2000s, we really can’t get around explaining why the network is the computer. It’s time to talk Sun Ray.

Sun Rays: the spokes

During most of its existence, Sun’s slogan was the iconic “The network is the computer“, coined in the early 1980s by John Gage, one of the earliest employees at Sun. Today, the idea behind this slogan – namely, that a computer without a network isn’t really a computer – is so universally true it’s difficult to register just how forward-thinking this slogan was back in 1984. These days, everything with even a gram of computer power is networked, for better or worse, and the vast majority of people will consider any PC, laptop, smartphone, or tablet without a network connection to be effectively useless.

Gage was right, decades before the world realised it.

The product category that embodies Sun’s iconic slogan more than anything is the thin client, and Sun played a big role in this market segment with their line of Sun Ray products. The Sun Ray product line consisted of a variety of products, but the main two components were the Sun Ray Server Software and the various Sun Ray thin clients Sun (and Oracle) produced between 1999 and 2014. The server component would run on a server (or workstation, as we’ll see in a moment), and the Sun Ray client devices would connect to said server over the network.

The idea was that you had a giant server somewhere in your building, running the Sun Ray Server Software, accompanied by whatever number of Sun Ray thin clients you needed on employees’ desks. Each of your employees would have a user account on the server, and could log into that user account using any of the Sun Ray thin clients in the building. The special ingredient was the fact that Sun Rays were stateless, which meant that the thin clients themselves stored zero information about the user’s session; everything was running on the server.

This special ingredient made some real magic possible, most notably hotdesking, which, admittedly, sounds like something LinkedIn professionals do on OnlyFans, but is actually way cooler. You could roam from one Sun Ray to the next, and your desktop, including all the applications you were running and documents you had opened, would travel with you – because they were running on the server. Sun also bet big on smartcards, so instead of logging in with a traditional username and password, you could also log in simply by sliding your smartcard into the card reader integrated into every single Sun Ray. Take your smartcard out, and your session would disappear from the display, ready to continue where you left off on any other Sun Ray.

And yes, you could make this work across the internet as well.

Reading all of this, you may assume Sun Rays and hotdesking involved a considerable amount of jank, but nothing could be further from the truth. I’ve been fascinated by thin clients in general, and Sun Rays in particular, for decades, but I never had the hardware to properly set up a Sun Ray environment at home – until now, of course. With the Ultra 45 all set up and running, and the generous Sun Ray-related donations from Adriaan and Volker, I had everything I needed to set up some Sun Rays. If the Ultra 45 is the central hub, Sun Rays are its spokes.

Let’s hotdesk like it’s 2007.

I expected setting up a working Sun Ray environment would be a difficult endeavour, but nothing could be farther from the truth. It turns out that installing, setting up, and configuring the Sun Ray Server Software is incredibly easy, and Nico Maas made it even easier back in 2009 by condensing the instructions down to the bare essentials (Archive.org link just in case). After following Maas’ list of steps (you can skip the personal notes section at the end if you’re not using a dedicated network card for the Sun Ray Server Software), any Sun Ray you connect to your network and turn on will automatically find the Sun Ray Server, perform any possible firmware updates, and show a login screen.

From here, you can log into any user account on the Sun Ray Server (the Ultra 45, in my case) as if you’re sitting right behind it. Depending on which generation of Sun Ray you’re using, loading your desktop will either be fast, faster, or near instantaneous. Thanks to Sun’s network display protocol, the Application Link Protocol, performance is stunningly good. Even on the very oldest Sun Ray 1 device I have, it feels genuinely like you’re using the machine you’re remotely logged into locally.

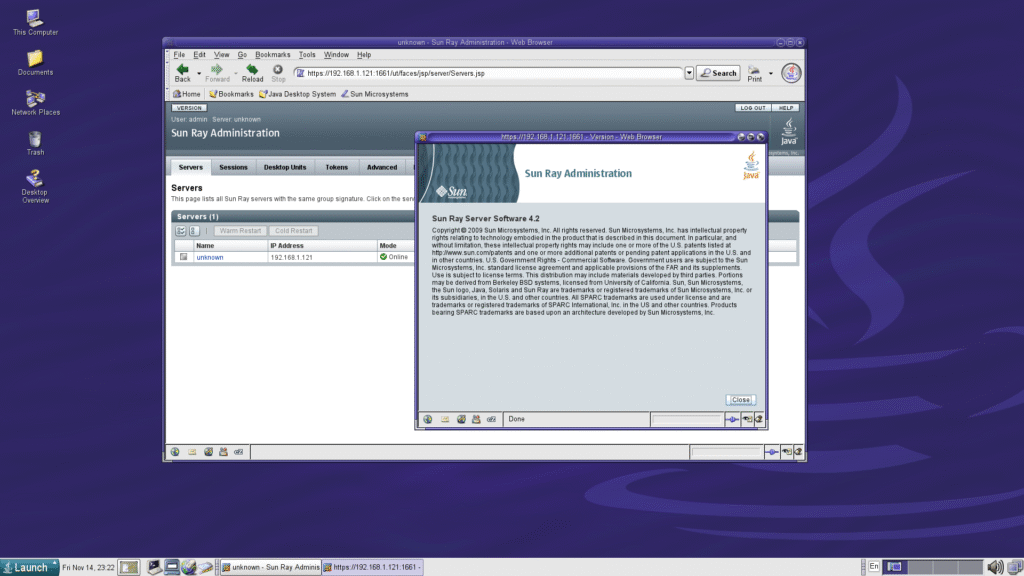

As part of Maas’ instructions, you also installed Apache Tomcat, included in the Sun Ray Server Software’s zip file, which is a necessary component for the graphical configuration and administration utility. Since we’re talking 2000s Sun, this administration GUI is, of course, a web application written in Java, accessible through your browser (I suggest using the copy of Netscape included in Solaris 10) by browsing to your server’s IP address at port 1660. After logging in with your credentials, you’ll discover a surprisingly nice, capable, and detailed set of configuration and administration panels, which mirror many of the CLI configuration tools. Depending on your preference, you may opt to use the CLI tools instead, but persoally, I’m an absolute sucker for 2000s enterprise GUIs.

While there’s a ton of configuration options to play around with here, the ones we’re looking for have to do with setting up smartcards so we no longer have to use bourgeois banalities like usernames and passwords. To enable logging in with a smartcard, you’ll obviously need a smartcard – I have a Sun-branded one, which are objectively the coolest – but there are other options. You’ll then need to read the token on said smartcard, and associate that token with your user account. As a final step, you need to utterly wreck the security of your setup by enabling passwordless smartcard login.

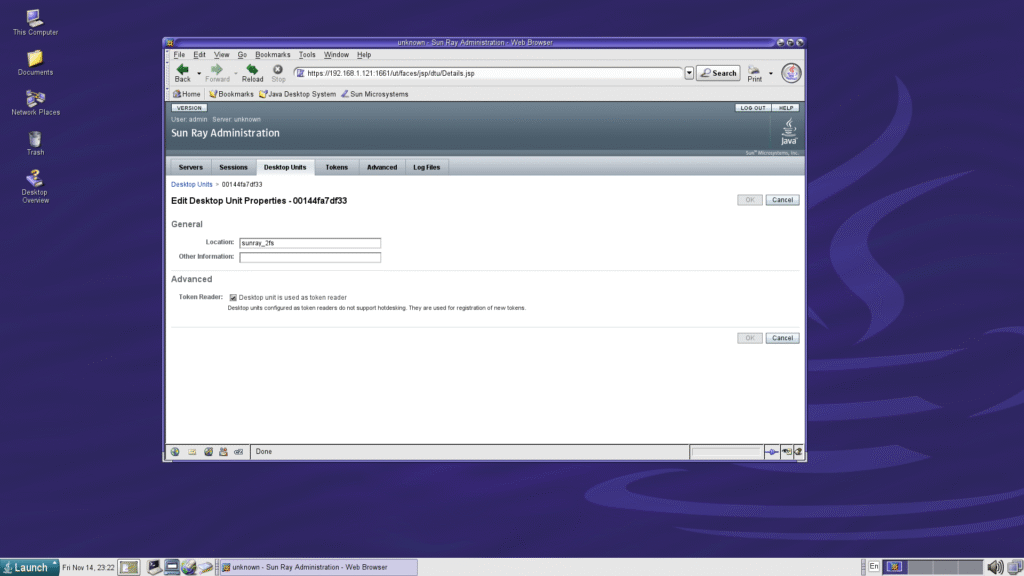

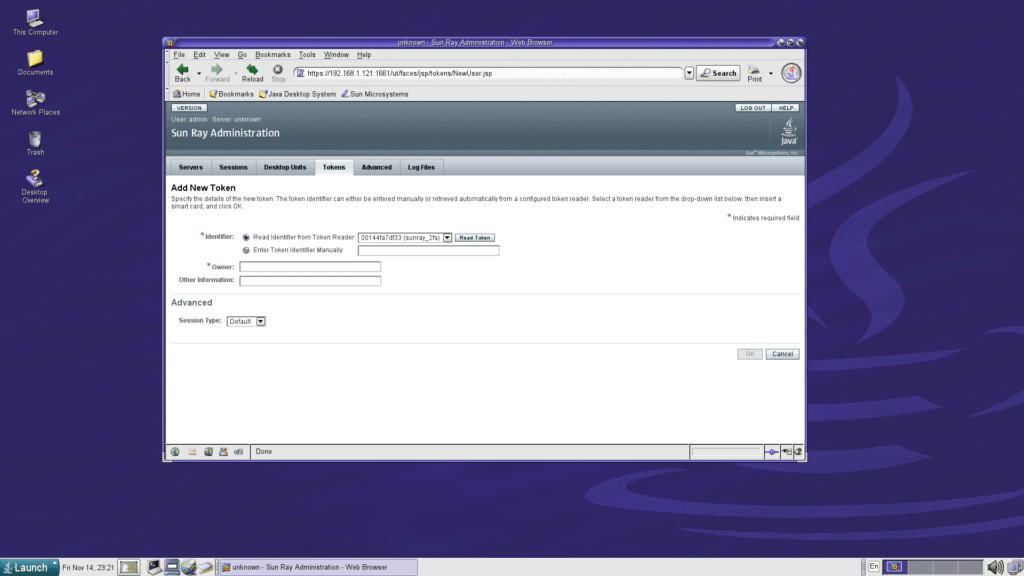

This process is fairly straightforward, but there a few arbitrary details you need to be aware of. First, you need to designate a Sun Ray as a card reader by going to Desktop Units, and selecting the Sun Ray unit you’d like to use as a card reader by clicking Edit and under Advanced, select “Desktop unit is used as token reader” – click OK and perform the cold restart of the Sun Ray Server Software as instructed. Once the restart is completed, make sure the smartcard you wish to use is inserted, then go to the Tokens tab, click on New…, and you’ll see that the token is already read and selected. Enter your username next to “Owner:”, and save. Make sure to undo the “Desktop unit is used as token reader” setting, and you’re good to go.

If you wish to log in entirely passwordless – as in, you just need to insert the smartcard, no typed credentials required – you need to go to Advanced > System Policy, scroll down to “Session Access when Hotdesking”, and tick the box next to “Direct Session Access Allowed”. It should go without warning that this is quite insecure, as someone would just need to yoink your smartcard to break into your account. For whatever that’s worth, on a retro environment in your own home.

Now you can properly hotdesk. Insert your smartcard into any connected Sun Ray, and your desktop will automatically appear, running applications and all. Take the card out, and the Sun Ray login screen will reappear. Wherever you insert your smartcard, your desktop will show up. This way, your session will travel with you no matter where you are – as long as there’s a Sun Ray to log into, you can continue working, even across the internet if that functionality has been enabled. Nothing about this is particularly complex technology-wise, but it absolutely feels like magic.

The clients

Let’s dive a little deeper into the Sun Ray clients. Sun (and later Oracle) produced a wide variety of them over the years, but roughly they can be divided up unto three generations. Disregarding the extremely rare early prototypes, the Sun Ray 1 is probably the most iconic model, as far as its design goes. It also happens to be the only model powered by a SPARC chip, the 100MHz microSPARC IIep accompanied by ATI Radeon 7000 graphics. The second generation switched from SPARC to MIPS, a 500MHz RMI Alchemy Au1550 (built by AMD) accompanied by ATI ES1000 graphics. The third generation of Sun Rays moved to either a 667MHz RMI Alchemy Au1380 for the base model, or the MIPS 750MHz RMI XLS104 for the Plus model, both with graphics integrated into the processor.

None of these core specifications really matter though, as the performance will mostly be identical. What really matters is the port selection, and the display resolution the Sun Ray unit is capable of outputting. I would strongly suggest opting for models with DVI output capable of handling at least 1920×1080, since full HD panels are easy to come by and you probably have a few lying around anyway. All models of Sun Ray have USB, audio, and Ethernet ports, so you’re good there, but the Sun Ray 2FS and Sun Ray 3 Plus also have fibre optic Ethernet options. You know, just in case you really want to go nuts.

Your eyes are not deceiving you. That’s a KDE-branded Sun Ray 2FS, and according to Adriaan, there’s only two of these in existence.

Sun also produced various Sun Ray models with integrated displays for that all-in-one experience, including one with a CRT. Beyond Sun, various third parties also made Sun Ray-compatible devices, offering form factors Sun didn’t explore, like laptops and even tablets. Sadly, these third party models seem to be exceedingly rare, and I’ve never seen one come up for sale anywhere. I would personally haul 16 tons and owe my soul to the King of Lanai’s company store to get my hands on a laptop and tablet model.

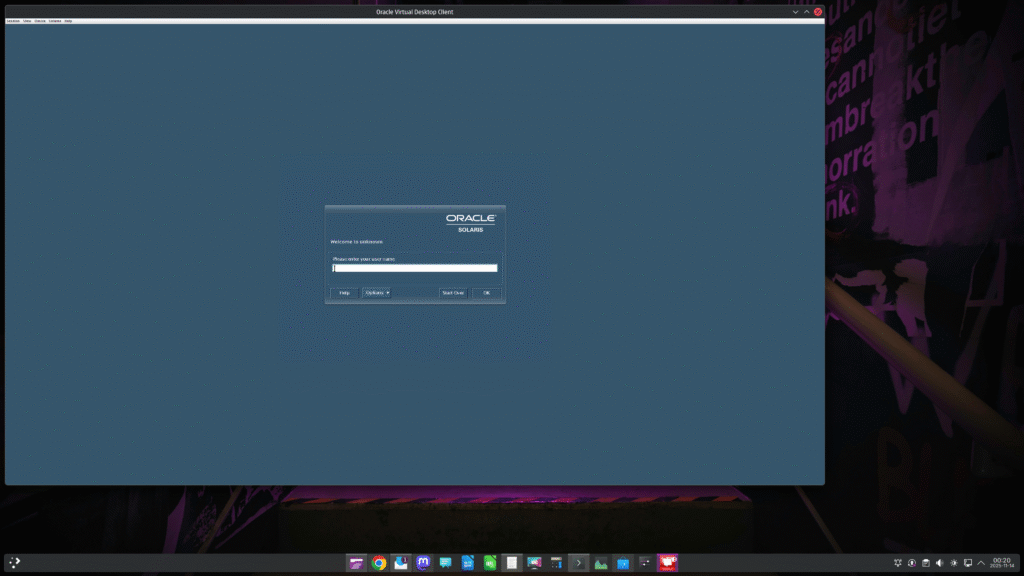

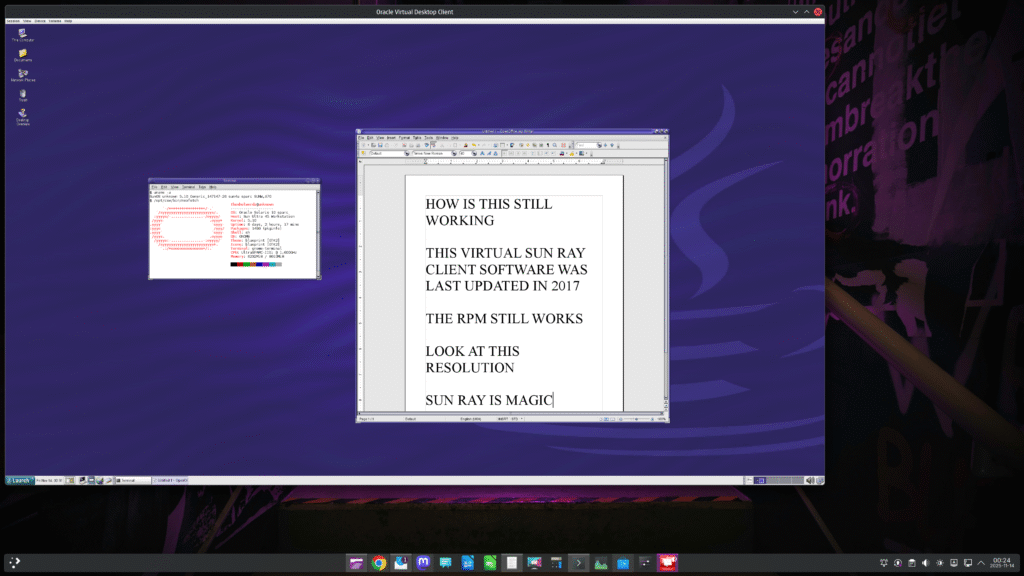

But what if you don’t want to deal with the hassle of real hardware? Thin clients or no, these things still take up space and require a ton of cabling and peripherals, which can be a hassle (I have three Sun Rays and their peripherals hooked up… On the floor of my office). Fret not, as Sun and later Oracle also released virtual Sun Ray client software, allowing you to log into the Sun Ray Server form any regular PC. Called the Sun Desktop Access Client or the Oracle Virtual Desktop Client, it’s a simple Java-based application for Linux, Solaris, Windows, and Mac OS, available in 32 and 64 bit variants. Alongside the entire Sun Ray lineup, this piece of software was retired in 2017, but it’s still freely available on Oracle’s website, given you manage to navigate Oracle’s byzantine account signup, login, and download process.

I only tested the version available for Linux, and to my utter surprise, it still works just fine! Since I run Fedora, I downloaded the 64bit RPM, and installed it with rpm -ivh --nodigest ovdc-3.2.0-1.x86_64.rpm. You’re going to need two dependencies, available from Fedora’s own repositories through the following packages: libgnome-keyring and libsnl. Once installed, the Oracle Virtual Desktop Client will appear in your desktop environment’s application menu, or you can start it with ovdc from the terminal. Before you start the application, though, you’re going to need to enable the option “Sun Desktop Access Client” in the Sun Ray Server Software web admin under Advanced > System Policy, and perform a warm restart.

You’ll be greeted by an outdated Java application, so on my 4K panel the user interface looks positively tiny, but otherwise, it works entirely as expected. Enter the IP address of the machine you’re running the Sun Ray Server Software on, and the login screen will appear as if you’re using a hardware Sun Ray client. I find it quite neat that this ancient piece of software – last updated in 2014, its RPM last updated in 2017 – still works just fine on my Fedora 43 machines. There were also Android and iOS variants of the Oracle Virtual Desktop Client, but they’re no longer available in their respective application stores, and the Android APK I downloaded refused to install on my modern Android device.

The Sun Ray ecosystem is, even in 2025, a versatile and almost magical experience. It’s incredibly easy to set up and use, but of course, effectively useless in that Solaris 10 and its GNOME 2.6-based desktop Sun Rays provide remote access to are outdated and lack the modern applications we need. Still, this entire exercise has given me an immense appreciated for what Sun’s engineers built back in the late ’90s and early 2000s, and I wish the Sun Ray ecosystem didn’t die out at Oracle alongside everything else island boy got his hands on.

But did it die out, though? Recently, I reported on the latest OpenIndiana snapshot, and wrote this:

A particularly interesting bullet point is maintenance work and improvements for Sun Ray support, and the changelog notes that these little thin clients are still popular among their users. I’m very deep into the world of Sun Rays at the moment, so reading that you can still use them through OpenIndiana is amazingly cool. There’s a Sun Ray metapackage that installs the necessary base components, allowing you to install Sun’s/Oracle’s original Sun Ray Server software on OpenIndiana. Even though MATE is the default desktop for OpenIndiana, the Sun Ray Server software does depend on a few GNOME components, so those will be pulled in.

↫ Thom Holwerda at OSNews

Now that you’re reading this article, it means the hold this project has had over my life has lessened somewhat, hopefully giving me some time to dive into OpenIndiana further. I’ve had issues getting it to boot and work properly on any of my devices, but knowing it’s still entirely compatible with Sun Ray means I might build a machine specifically for it. The sun must shine.

Conclusion

Could Sun’s ecosystem have made for an excellent computing environment at home? I’m realistic and realise full well that nobody was going to buy an expensive Ultra 45 or otherwise set up a SPARC server with a SunPCi card and Sun Rays just for home use. These were enterprise products with enterprise prices, after all. Still, I think the basic idea of a powerful central computer in the home – perhaps a server in the utility closet – accompanied by a number of cheap thin clients is sound. Most of our computers are sitting idle most of their lifetime, and there’s really no need for every member of a household having access to their personal overpowered desktop and/or laptop.

Twenty years ago, Sun’s ecosystem showed us that such a setup need not be complex, janky, or cumbersome, and with a bit more end-user focused polish it would’ve made for an amazing home computing environment. Of course, there’s far more profit to be made in selling multiple overpowered computing devices to each consumer, especially if you can also manage to force them into subscription software and “cloud” services, while showing them ads every step of the way.

I’ve only scratched the surface of everything you could possibly do with the hardware and software covered in this article, as I didn’t want to get too bogged down in the weeds. There’s other operating systems to try on the Ultra 45, there’s compatibility to explore with the SunPCi, there’s OpenIndiana to install to see just how hard it is to get the Sun Rays working with a modern operating system, and, of course, there’s a ton of finer details to tweak, fiddle with, and discover. I haven’t had this much fun with a bunch of computing devices in ages.

This deep dive into Sun’s ecosystem has consumed most of my life over the past few months. I know full well writing 10,000 word articles on dead Sun tech from the 2000s is not a particularly profitable use of my time. This isn’t going to draw scores of new readers to the OSNews Patreon and Ko-Fi and make me rich. For profit, I should be making YouTube videos with fast transitions and annoying sound effects to stir up drama based on GitHub discussions or LKML posts with my O face in the thumbnails.

But someone needs to show the world what we lost when Sun died and the industry enshittified. Tech has hit rock bottom, and I want to show everyone that yes, we can build something better.

We only have to look back at what we lost, instead of forward at what’s left to destroy.

We were donated a Sun Ray server + 24 (?) thin clients when I was still at college. I was part of the (volunteer) team in charge of setting them up.

It “worked”, but nobody used them. CDE was already obsolete, and we had Windows NT and CentOS Linux workstations that students preferred which were much mode modern, and easier to use.

After a SUN update, we were able to get some rudimentary GNOME install on them. However this time, while students really started to use the lab (especially when single sign on was working with out LDAP servers)… it was extremely slow.

So, while the idea is interesting, serving 20+ clients from a single server could not keep up with having a lab full of semi decent PCs which can run Windows NT (2000?) and Linux at native speeds.

The main issue with Sun Rays was that they were DOA. They had little value proposition at the rate commodity HW prices were behaving. So in the end a gimped Sun Ray was more expensive, to the intended customer, than a PC, for example.

The old unix vendors (Sun, SGI, DEC…) just did not understand economies of scale for whatever reason. So by the end of their runs, they were proposing products that simply did not make sense from price/performance points.

When I was @ SUN, we didn’t know what to do with the Sun Rays, other than being an emergency access point for some file or as a demo head at a conference room. And neither did management know what these things where for or for what actual use case enough clients wanted them.

Like a lot of stuff @ SUN it seemed like a project that had gestated for far too long, as an idea that started in the late 80s or mid 90s. It was basically a glorified Xterminal with a smartcard reader, and a slightly more “intelligent” back end on the server side.

But by the time it made to market, it just made little sense. A PC running linux was a more performant local workstation than a Sun Ray for cheaper. And in many cases the PC had a more powerful processor locally, than the SPARC CPUs in the server the Sun Ray was going to be hanging off anyway.

Xanady Asem,

To be honest, I was not subject to Sun Ray pricing, as the lab was donated to our department. However this makes it even more sad, as it was the least used lab among many.

Btw, seeing someone from Sun with insight knowledge is nice.

I think I can understand the struggle where there is no urgency to the market, and project that “succeeded” to launch fails to move the needle for the company.

I sat on Enterprise Consumer side of a business during this era that was heavily invested in Sun and Oracle. I am in agreement with Xanady Asem on the Sun Ray’s. They sat around our compute offices, almost always idle. If they couldn’t win this audience, what path did they have? Server hardware was good, and Solaris was reliable, but often costly Some of the toolset was buggy, which our internal teams managed to work around this. The handwriting was on the wall for us shortly after the Oracle buyout.

To be fair the handwriting was on the wall way before Oracle.

I was w the SPARC team during Rock, and it became abundantly clear that we were basically 1 decade behind in terms of bringing SPARC to the out-of-order era. X86_64 was cleaning RISC’s clock in single thread performance, for a fraction of the cost. And for the high throughput stuff, Niagara simply made no sense, because customers were just putting together a bunch of cheapo commodity boxes that were serving the same throughput per rack, again at a much much lower price point. The expensive fancy RAS stuff we were doing for the box, they were getting for free at the rack level. Which is all that mattered.

The irony is that in the end SUN actually never understood their own motto: the network was in fact the computer. And they simply missed the boat of the truly distributed high scale era that was coming up. Even though technically they were an early adopter of what ended up being cloud computing (SUNGrid)

Internally SUN was way too caught up with “Unix” purity, and ended up also missing the Linux train.

It is fascinating how culture can be an organization’s main asset initially, but it can become it’s albatross around its neck. SUN was an avid proponent of open systems initially, yet they ended up having a very partial vision of where open systems were truly going and refused to adapt.

Xanady Asem,

Google demonstrated a networked collection of commodity Linux hardware can match, and easily surpass specialized system by a wide margin.

And they used very simple Linux setups, and the famous “map-reduce”.

Though, they had to implement cgroups, which later led way to docker, their internal cluster manager Borg was never available to the public (even GCP uses a “washed down” version called Kubernetes).

And map-reduce gave way to Hadoop (which was infinitely inferior, but every undergrad knew that, and very few knew it was actually a poor clone of what Google did internally)

Anyway, today, Kubernetes + Beam pretty much dominates high performance data processing. And except maybe IBM and Oracle which hold onto tight support contracts, commercial UNIX has been replaced.

Thom Holwerda,

The company failed to stay afloat, which is a shame, but the fruit of their work and innovation still lives on, continuing to be ported and worked on.

We used Sun pizza boxes at university. I think most of us spent more time accessing them remotely than in the labs. This gave many students a huge appreciation for X’s network transparency. This was such an important connectivity feature with solaris, but it likely became much less important as more began running linux at home. I get the impression many linux users never experienced a need or appreciation for remote X sessions.

Thanks to the use of distributed file systems, it really didn’t matter at all which machine you logged into, your entire profile along with all your files were there automatically. Even to this day I miss that feature. Microsoft never got a similar feature working as well as Sun did. The best approximation is to use windows terminal services, but that’s a remote thin client solution, not natively running your software on the local machine.

My main gripe with these university accounts was file quotas. They were unwilling/unable to provide unlimited disk space, haha. This meant having to purge files regularly to do new classwork.

Also, while admins probably felt this was a “feature” rather than a con, unix POSIX file permissions are very limiting for group collabs. As users we couldn’t share files on our own terms, admin intervention was always required for group projects and having worked with windows workgroups I’ve always felt (and still feel) that linux file sharing capabilities are worse and more difficult than on windows.

Anyway I remember Sun fondly. They were good at technology and Sun’s gifts to FOSS gave us technology we wouldn’t otherwise have. But they clearly struggled with business models and ultimately could not compete against cutthroat tactics by stronger competitors. Oracle taking them over is a harsh lesson in Darwinism – being the good guy doesn’t mean you’ll win. As much as it disgusts me, anti-owner restrictions, enshitification, DRM, etc might be the better play from a “survival of the fittest” point of view. Look at the types of companies most rewarded by the market, many at the top are actively promoting the enshitification of tech 🙁

Alfman,

If you did not care too much about absolute privacy, one could always give group read permissions. But write is always an issue. (We fixed that much later in Linux with ACLs + OpenLDAP)

(Assuming all students are in large “stu” or similar groups).

Yes, their ZFS is still used in many modern storage systems.

And I would also send a regards to SGI. Their work on C++ containers is what “saved” the language (and later became STL).

What’s more? I fondly remember seeing “Property of Silicon Graphics Interactive” on a large trash container in the Google Campus (GooglePlex used to be SGI campus)

Great article. The loss of Sun with support for SPARC/Solaris/etc was huge.

I used/played/ even worked with an Ultra 60 & E1000 at home early 2000’s. E1000, as a quad 167MHz ran a sun ray 150 as its only ‘head’, included being capable of video file playback. Not HD of course but that it worked at all, on that hardware and topology I could only account for as sorcery. I was fine with CDE, though even the U60 didn’t love gnome.

Despite some HW releases post-2000, I think in that timeframe everyone else knew they were dead (or diversifying in preparation). It was performant enough (vs a few year newer dual P3’s, banias, P4), & Sun had so many good pieces of the stack. I felt like they had a chance to hold on in enough places to not sell out to say, IBM or someone worse e.g. oracle. And- really good support for OSS software ports and, was actually stable.

Serial installing solaris to systems in another country was easier then than now, by some godawful ilom. Imagine if a whole system had been designed for management. But you sure knew when you opened one of the applications that they’d rewritten in Java.

U60 & SunPCI II was kind of a HW accelerated virtual machine. One extra distcc node.

I’m pleased/surprised SRSS & other software has had a better afterlife than it seemed. But I’m pleased more, to still be using some of Sun’s legacy, zfs, nfs (vi, if you don’t want to quibble) every day.

~#

Our university used to have an earlier version of such a system in the early noughties. I distinctly recall having worked with similar clients (though, they were slim desktops) in the computer room.

A boring experience (which is good) where I didn’t even realize that it was unusual in any way ^_^

Super work Thom! I really like how you wrote this – accessible, personal, detailed and straight without doing the modern manipulative thing. This is what the internet should be.

I trained on HP-UX in the early 2000s, and I’m pretty sure the server was PA-RISC since Itanium had only just come out. I’ll never forget that classic CDE default theme. We worked with the Korn shell, and when I later bought an iBook G4 running Mac OS X 10.3, I was amused to find that ksh was the default there as well.

HP-UX isn’t completely gone yet, it actually reaches end-of-life next month.

While MacOS isn’t used by most people as a UNIX workstation, it is by a LOT of scientists including a lot at NASA because it is the easiest UNIX workstation plus has much better security than Linux does.

I took missed using Solaris. We have several workstations that people used for GIS (“Geographic information system” for those people that don’t know what it is) which within a year was made to work on Windows and the UNIX workstations went away because they were too expensive to upgrade/replace.

My exposure was with Linux and the UNIX shell on Apple computers. Though I admit that OS/2 spoiled me and I just never fell in love with Linux/UNIX the way I did with OS/2 and REXX and the speed and reliability with OS/2 that was FAR superior to Windows.

And by the way, for anyone that says, “But I can easily cause OS/2 to crash” I can easily say that MILLIONS of people deal with Windows crashes every day so I’m not impressed. What is _impossible_ is not rebooting Windows every month. Meanwhile I have an OS/2 computer and I use every day along with Mac that has been up and running for five years without a reboot and without a virus on it. That’s literally impossible on a Windows machine.

But this is about UNIX and specifically about Sun Microsystems. Just as I had someone that had used Solaris for five years was starting to teach me about them, the organization I worked for (over 17k employees) sold them.

I’ve always loved using a multitude of different OSs and different systems. I used have three different brands of servers with different types of OSs with three different networking topologies at home where I had all of them communicating using five different PCs with three OSs on each computer that I could reboot and choose which OS I wanted to use on that boot session.

I loved that part of my life. Then I started having health issues that really f’d up my life making it hard to deal with one system let alone all of the ones that I had and when power supplies failed, I didn’t have the energy to buy new ones and keep things up and running. The late ’90s were a GREAT time and a HORRIBLE time at the same time.

I almost died. OS/2 almost died (for anyone that is interested, check out https://www.arcanoae.com/ which has a license from IBM to keep drives up to date for new hardware). And I HATE Microsoft with a passion for being the cause of BeOS and other OSs and desktop software companies selling their products to other companies because they were tired of fighting against evil MS. And now we have a president that I hate as much as the former CEO of MS. Oh boy! 🙁

All I can say is that I’m jealous (in a good way) of Thomas having the health and energy to do the kind of things of what I did in the 1990s.

So I often use some Sun systems on the mid-2000’s UltraSparc machines (especially Sun Fire v240/v210 machines), and my experience has been that Linux is kind of a disaster there. But a huge surprise has been that even better than Solaris 10 is OpenBSD. Everything *actually* just works, and maybe that shouldn’t be a surprise. A lot of OpenBSD’s early popularity grew from Unix admins using systems like Solaris boxes who wanted a free alternative, and so a lot of effort went into making those machines work properly.

OpenBSD is the only OS that, without any extra configuration, will boot into a graphical session if a Sun Fire system has a proper video card installed. That alone is kind of mind boggling to me.

Incredible work, Thom.

I too am growing my collection of classic Unix workstations. I just picked up a Sun Blade 150 a couple of weeks ago. It’s going to take some work to get running, as the NVRAM module is dead and I have yet to solder on a working battery. I think its booting to the serial console but I’m waiting for a serial-to-usb adapter to arrive to check.

I also have a couple of PPC Apple computers. MacOS X is technically UNIX, so, I’m counting them.

My biggest pain is that we shifted from trying to “make a lot of money through a better product” to “make a lot of money”.

Microsoft played dirty in the 90s, but they did a great job nonetheless with Windows 95 and their commitment to backwards compatibility is amazing (I can rock the original software of my 2005 film scanner without any problems and it even scales decently to high DPI).

We had tons of CPU architectures to choose from. Perhaps there was no room in the market for all of them, but I think there’s room for more than amd64/arm (and a bit of risc-v).

nextstep is incredible for what it does on the limited hardware that supported it.

And yes, some companies would run thin clients, others a fleet of laptops, others stationery workstations, some would use Domino, others Outlook, others a mix of open source stuff.

Now we get bloated webapps that cut to a third the battery life of my laptop. =( It is just so incredibly boring, and whatever comes out is so unpolished and buggy and slow and disrespectful to the user. It is just sad. My excitement for tech has pretty much died.

People focus too much on the ISA as it being the “architecture” when that has been decoupled from the internal architecture for most modern CPUs for ages.

Once you get past that bias, you have actually far more different architectures than almost any other time. And this time around, we can afford most of those CPUs;-).

As per the buggy bloated software, that has always been a constant. I remember as a kid, a simple text-based accounting package would bring a high end PC to its knees @ my parents office.

Thank you for this article, which highlights how we’ve neglected some excellent solutions in favor of commercial products, ultimately resulting in a less than pleasant user experience.

Solaris is a great OS.

Beautiful article. 25 years ago I had a habit using my fresly acquired internec access at Uni to wander thru SGI and Sun webpages, especially focusing on workstations. Sad thing – that now – when I am technically position that would enable me to work on such kind of hardware… all I got is Lenovo Thinkpad.

Awesome!

Thanks for the article; it’s nice to reminisce about the good old days at university. I remember about 25 years ago. I was in my last semesters of the computer science program at my local university. I was pretty good with Unix, and of course, no one else had a clue how to use it. So, the head of the computer lab building asked me to help install and configure some Unix servers. We had SGI servers, Alpha servers, and, of course, Sun servers. One day, Sun technical support came to the lab and installed a couple of Sun servers and clients. When they were finished, the building manager gave me one of those Sun smart cards, but he never told me what to do with it or how to use it. I suspect he didn’t even know himself. But hey, it looked pretty cool, so I kept it for 25 years.

And 25 years later, I finally know what those smart cards are for..

You should remove one of the cache devices and add it to the pool as a separate intent log device (ZIL). That way, writes will be written to flash first, then copied over to the spinning disk, along with using the cache devices for speeding up subsequent reads.

zpool remove poolname cachedevice

zpool add poolname log cachedevice

You might need to use a mirrored log vdev, as I don’t remember if ZFSv28 (which I think is the version in Solaris 10?) supports booting a pool with a missing ZIL vdev.

zpool remove poolname cachedevice1

zpool remove poolname cachedevice2

zpool add poolname log mirror cachedevice1 cachedevice2